Islands of Temptation: Indonesia's Private Water Lessons

International water management – involving tariffs and local customers – can be a political minefield, as found out in Enron's Azurix case in Argentina. So is there still room for the private sector in Indonesia after the Thames Water and Suez Environnement's experience? As Jeremy Josephs reports, the market should be handled with care.

There can be little doubt that the experiences of Suez Environnement in Jakarta have been anything but happy. Quite the contrary in fact. For the Paris-based utility giant recently sold its 51% equity stake in the West Jakarta water concession to Manila Water, following a complete breakdown of relations between the concessionaire and PAM Jaya, the public water authority, over ongoing tariff freezes. One PAM Jaya director was replaced with another.

The strained business relationships in Jakarta were the subject of a letter from the CEO of GDF Suez, Gérard Mestrallet, to the Indonesian Coordinating Minister of Economic Affairs. And in an even clearer indication of the economic and political stakes involved - as if one were needed - the situation was even discussed at a meeting between no less than the former French Prime Minister Francois Fillon and the President of Indonesia himself.

But not even these extremely high level interventions, it seems, could prevent a rather acrimonious divorce from taking place. Which prompts one to ask, of course, not just how it all began but how it became possible for relationships to breakdown so catastrophically? And what lessons, if any, there are to be learned?

Privatisation prodigies

One can hardly claim that the founding fathers - or parents, perhaps - of privatization are Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher on the not unreasonable grounds that the history of contracting virtually everything out to the private sector can be traced right back to ancient Greece. Still, were it not for the fact that the 40th President of the United States is no longer with us and that Mrs Thatcher is currently battling against Alzheimer's disease, one could well imagine those erstwhile articulate advocates of the virtues of the private sector positively rubbing their hands with glee at what was happening to the water sector in the Indonesian capital back in the early 1990s. It was a carve-up. And a twenty five year carve-up at that.

With key multi-lateral (World Bank) and bi-lateral (Japan) loans in place, Suez and UK utility Thames Water moved in. This was back in the days of the former Indonesian President Suharto's dictatorship which meant that doing business in Indonesia meant doing business with a local firm.

And most local firms – surprise, surprise – were controlled by the Suharto family. Which in turn meant that Thames Water and Suez were obliged to hop into bed, so to speak, with the Sigit (controlled by Suhatro's eldest son) and Salim Group (controlled by Anthony Salim, a Suhatro business crony) respectively.

Fast Facts: Indonesian Water Sector- Indonesia has abundant water resources along with rapid urbanisation and a minimal water provision and sewerage infrastructure. Water supplies to cities have been affected by catchment degradation, conflicts between urban and agricultural use, untreated sewage and the lack of regulation of the discharge of industrial effluents. - According to the Public Works Ministry the current sanitation budget is RS3trillion (USD318 million) per annum (Jakarta Post 27th June 2012). - Freshwater : annual withdrawal : 3%. Domestic : 8%. Industrial : 1%. Agricultural : 91% - Groundwater : Total recharge : 226 km3 |

There was no open and transparent bidding process, despite claims by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank that they promote "good governance" and transparent privatization transactions.

It would be something of an understatement to say that these two contracts got off to a bad start. For even though they foresaw water charge increases that would allow the European investors to earn a very comfortable 22% rate of return, thank you very much, after just eight weeks two rather traumatic events took place: the Indonesian rupiah went into freefall because of the East Asian financial crisis and the dictatorial Suharto was given his marching orders.

While the concessions survived, the new government moved swiftly to impose a tariff freeze. In turn, this meant that the contracts had to be renegotiated to reduce their targets. Thames Water got out swiftly and Suez dragged its heels a little longer. Its Indonesian operating.

Project stagnation

For consultants in the Indonesian water sector, such as Océane Trevennec, International Agro Development expert, who heads up various Franco-Indonesian partnerships, and who was herself based in Jakarta for four years, all of these shenanigans represent a series of wasted resources and missed opportunities.

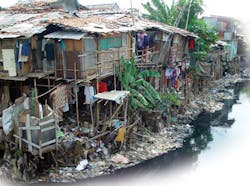

"Being the capital, Jakarta is of course the centre of political and economic power but where a rapidly increasing population remains overwhelmingly poor," he says. "So to take up the challenge of water management services in the capital means that you find yourself at a place where political, economic and social pressures meet – not an easy place to be.

"What this has tended to mean in practical terms is that political and economic issues have the upper hand – in other words that water supply and sanitation projects stagnate. This in turn means that environmental issues continue to deteriorate – and fast. This becomes something of a vicious circle with environmental problems such as pipe projects becoming more difficult from a technical point of view – to such an extent that I really do fear that the point of no return in terms of Jakarta health impacts might not be so very far away."

Trevennec highlights that basic needs should be prioritised before international business co-operations.

"This is a great shame because I also happen to believe that the synergy of skills between water giants such as Suez Environnement and local Indonesian teams would have been able to meet these challenges," she adds. "But these public-private partnerships have clearly not worked out well in this instance. My own view is that before we think about how water management services can represent a lucrative business, we should firstly think about how to meet basic human needs in terms of drinking water access and sanitation, as we are in fact obliged to do under international law."

Water loss reduction

The acid test of all of this is not the issue of ownership but something altogether far more pragmatic - whether or not the good citizens of Jakarta were being well served by water and waste service companies - whoever that provider might happen to be. In fact both Thames Water and Suez, during the concession years, managed to increase the share of the population with access to water and they duly reduced water losses in line with their renegotiated contractual targets.

In the 10 years from 1998, access to water in Jakarta increased from 46% to 64%, while water losses were reduced by 11% to 50%. And although it is true that private companies did indeed attempt to improve the supply of clean drinking water to slum areas where house connections are difficult, these attempts were fairly limited and their results, at best, can only be described as poor. Suez Environnement's Palyja installed meters, from which residents in communities were to be able to connect themselves with the assistance of NGOs such as the Mercy Corps. But to this day it remains a sorry story - there are still only three "Master Meters", one in Rawa Bebek and two in Jembatan Besi.

In fact nearly half of Indonesians live without sanitation or clean water. Few people are familiar with the fact that Indonesia is in fact the fourth most populous country in the world – which means that over one hundred million souls go without provisions which, back in 2010, the United Nations officially declared to be a basic human right. The country's Health Minister Nafsiah Mboi has admitted that "the disparity between access to sanitation and clean water in cities and in villages means that we are still far from achieving our accessibility targets." She noted that 76% of urban residents had access to sanitation and clean water, compared to 47% of rural residents, who account for the majority of the country's population.

The thorny issue of price

Renalia Iwan has her own ideas as to why. In a thesis submitted to the University of Wellington, she took a long and hard look at the Thames concession - Thames PAM Jaya, to give it its full name. Her conclusions were rather damning and, one cannot help wondering, had her words been listened to, whether or not Thames Water would have beaten such a hasty retreat from Indonesia altogether.

The thesis states: "Ten years of private sector involvement in Eastern Jakarta Water Supply Provision has not brought any significant improvement in the water service and high Non Revenue Water continues to make up 52% of total production. This is mainly due to hostile attitudes towards the managers of the service built up around the sense of unequal access to water especially on the part of the poor. Thames PAM Jaya like other private enterprises is profit oriented and therefore focuses exclusively on customers who are able to pay for connections but by excluding the poor create trouble for themselves."

Suez Environnement's battles were more closely related to the issue of price. Prior to packing his bags and heading home to France, Philippe Folliasson, in his capacity as president director of the PT Pam Lyonnaise Jaya (or Palyja as it is commonly known) had said that his company planned to invest Rp 850 billion (some $84 million) in new water infrastructure and repairs. But in return for so doing would require an increase in the water tariff. This money was to be spent connecting 25,000 consumers, providing booster pumps and renovating existing plumbing to minimize leakages. A not inconsiderable amount of this was allocated to rehabilitating some 75 kilometres of pipes in the existing – but decaying – networks.

In return a 22.7% increase in the water tariff would be required. It was this tariff hike request which proved impossible to resolve, despite the best efforts of the Jakarta Water Regulatory Body, and others to act as mediators and impartial intermediaries. It might well all have been set out in black and white in the contract between the two partners to the agreement in the first place – but actually implementing its terms and conditions was clearly proving to be a difficult pill to swallow in Jakarta.

"All of this demonstrates the key importance of properly negotiating the contract in the first place", says Jean-Antoine Faby, who heads up the prestigious 'Water For All' training programme in France. "To me when it comes to water services the heart of the issue is that we need to instil the notion of running everything from a professional business point of view. What does this mean in practical terms? That the customer should be at the very heart of the matter. And where the notion of service is the core value? This means that senior management needs to have its eyes and ears wide open."

Water professional Didier Perez - another expert in Indonesian water and who heads up both PT.Pipa Indonesia and the Air Kita Foundation - would certainly go along with that. Except he expresses himself somewhat more forthrightly. "I was in Indonesia in February 1998 and witnessed all of this privatization. I became an actor as well as a victim of the whole process. Until, that is, being invited to the obituary. I am pretty certain that the whole debacle will be debated in most business schools around the world. Why? As a typical show case of what should be avoided when it comes to public and private partnerships."

Burnt bridges or Indonesian opportunities?

With Suez Environnement's man in Indonesia now back in Paris – and with Thames Water similarly long since gone from Jakarta, does this mean that we are at the end of the road when it comes to the joint ventures and investment in this particular part of south-east Asia? Hardly. For just a few weeks ago GDF Suez, the world's largest private utility company, opened an office in Jakarta, making a clear statement of claim as to the firm's efforts to expand its business interests in the region's largest and most vibrant economy.

Willem Van Twembeke, chief executive of GDF Suez Energy Asia, says that GDF Suez "considers Indonesia an extremely important country and a part of the firm's international business development." And he went on to note that it was the sheer geographic size of Indonesia, coupled with its growing economy, which continues to make it such an attractive destination for prospective investors.

True, this is all about power. And oil and gas. Not water. But those with long experience in the water services sector have little doubt that it won't be too long before other leading European operators will return. Not necessarily Thames Water and Suez. But when it comes to prospective foreign investors in Jakarta's troubled water sector, it's almost certainly a case not so much of adieu Indonesia – but rather a simple au revoir.

The answer is spelled out pretty clearly on Palyja's website under the heading 'Our Challenges – Need for Alternative Funding'. It's not in the world's best English – but the message nevertheless comes through loud and clear.

"Funding sources for major investments relating to enhancement and increase of water resource and implementation of transmission lines to the area with outstanding demand; either via co-financing through regional budget, central budget or IFIs (International Financial Institutions) and donors contributions, have to be mobilized." Oh yes, it's au revoir indeed.