Recent and pending state and federal water legislation impacting the water and wastewater industry

Long before the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was founded in 1970, the U.S. was concerned about protecting its waterways and therefore enacted the first piece of legislation in 1899: The Rivers and Harbors Act, designed to prevent dumping of refuse into waterways.

Since then, numerous laws have been passed and regulations established — and yet, every year, more are introduced, with good reason. According to an EPA spokesperson, “The nation’s water resources are the lifeblood of our communities, supporting our economy and way of life. Across the country, we depend upon reliable sources of clean and safe water. Just a few decades ago, many of the nation’s rivers, lakes, and estuaries were grossly polluted, wastewater sources received little or no treatment, and drinking water systems provided very limited treatment to water coming through the tap.”

Today, more than 90 percent of the population has access to safe drinking water from community water systems regulated by EPA or delegated states and tribes. Nevertheless, while significant progress has been made, water resources, water infrastructure, and other emerging challenges remain.

Lead and Copper

Based in part on input received from the Science Advisory Board, the National Drinking Water Advisory Council, state and local partners, and peer-reviewed science, the EPA proposed an update to the existing Lead and Copper Rule to identify the most at-risk communities and ensure systems have plans in place to take actions to reduce elevated levels of lead in drinking water.

“Lead was used for service lines for years,” acknowledges Tommy Holmes, legislative director for the American Water Works Association (AWWA). “Now we know that’s bad.”

David LaFrance, AWWA’s CEO, considers it “a necessary first step in developing plans to remove lead service lines and helping households and community leaders understand the scope of the lead challenge.”

The new rule emphasizes the importance of corrosion control and requires utilities to take corrective steps if household sampling suggests a lead problem. “The new LCR is an opportunity to build on decades of progress in reducing lead exposure,” LaFrance proclaims, citing a “dramatic reduction in lead exposure” over the past 45 years.

It’s the first major overhaul of the LCR since 1991 and improves protocols for identifying lead, expanding sampling, and strengthening treatment requirements in order to prevent lead exposure, especially in the most at-risk communities. When finalized, this proposal will require more water systems to act sooner to reduce lead levels.

Actions community water systems would be required to take include:

• Identifying the most impacted areas by preparing a publicly available inventory of lead service lines and fixing sources of lead when a sample in a home exceeds 15 ppb;

• Strengthening drinking water treatment by implementing corrosion control treatment;

• Replacing lead service lines;

• Increasing drinking water sampling reliability by using improved sampling procedures;

• Notifying customers within 24 hours if a sample collected in their home is above 15 ppb; and

• Taking drinking water samples from area schools and childcare facilities.

In addition, EPA is proposing a lower lead trigger level of 10 ppb, which would compel water systems to set an annual goal for conducting replacement of systems above 10 ppb but below 15 ppb and annually replace a minimum of 3 percent of the systems above 15 ppb.

PFAS and Other Contaminants

EPA is also addressing emerging contaminants such as polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and is working on a national drinking water regulatory determination for PFOA and PFOS, a spokesperson indicates.

PFAS comprises a large group of environmentally persistent, man-made chemicals used to fight fires and to produce medical equipment, food packaging, cleaning products, nonstick cookware, stain- and water-resistant coatings, paints, inks, and cosmetics. There are 3,000 compounds, and while hundreds have been banned, 600 are still being produced.

PFAS doesn’t break down easily in the environment. Uncontained runoff migrates through soil and contaminates nearby aquifers and surface waters; it is also found in leachate at landfills. PFAS is known to cause adverse health effects at very low concentrations. Two PFAS compounds, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid and perfluorooctanoic acid, have been found in drinking water.

“PFAS and lead are the contaminants of greatest concern,” Holmes states. AWWA’s 2019 State of the Water Industry Report lists PFAS as the second-highest ranking regulatory concern. “There’s always an issue of emerging contaminants; this year it’s PFAS.”

He said that since passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act, immediate public health risks are controlled. “Now we’re looking at long-term health risks.” Unlike a microbial contamination that makes people sick quickly, PFAS has a long-term exposure effect.

In December 2019, the Senate approved the final version of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which included key provisions regarding the use of PFAS going forward. Specifically, under the new bill, the military will be required to phase out the use of PFAS over three years. The legislation also calls for nationwide testing of all drinking water supplies in the country, not just those serving more than 10,000 people as was previously required. At the time of this printing, President Trump was expected to sign it into law by the end of 2019.*

A hazardous substance designation could increase the risk of litigation, Holmes believes. With existing treatment techniques, water systems dispose of PFAS residuals by applying biosolids to farmlands in the form of sludge or injecting residuals into wells. “If it has PFAS in it, even though the utility is not the source, they’re liable.”

Scientists want to wait for methodology and processes to determine the need to regulate PFAS, but Congress is pushing for legislation on both lead and PFAS. AWWA is in the middle.

“We want to protect the public health, but not divert resources away from known risks that are more urgent,” Holmes explains. “We want the scientific process to play out.”

State Action

While Congress considers legislation that would require national regulation of PFAS, PFOA, and PFOS under the Safe Drinking Water Act, delays have resulted in 12 states making their own regulatory policies. Further, 17 states have source water protection policies for PFAS. New Hampshire has the strictest PFAS standards, although they’re still significantly lower than the EPA’s level. State-ordered PFAS testing is beginning in California.

There are a lot of issues in California, said Ellen Hanak, director of the Water Policy Center for the Public Policy Institute of California, a non-partisan research institute. The big one, she said, is safe and affordable drinking water, whether contaminated by arsenic, nitrates, or other chemicals or simply facing shortages.

“We’re working to fill funding gaps in poor communities,” Hanak said.

The Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Fund was signed into law in 2019. The allocated $130 million per year over 10 years is currently being used to establish an advisory council to determine how to use the money.

Two new laws address water quality and supply, especially in low-income and rural areas. Assembly Bill 508 authorizes the State Water Board to order water system consolidations in communities where domestic wells consistently fail to provide safe drinking water. Senate Bill 513 authorizes the Board to provide immediate relief to households where wells have gone dry due to drought or disaster.

Two more new laws focus on improving the health of the freshwater ecosystem. Senate Bill 19 addresses a data gap in the management of water for ecosystems and requires the Department of Water Resources and the State Water Board to modernize and expand the state’s stream gauge network. Assembly Bill 834 establishes a program to mitigate harmful algal blooms in rivers, lakes, and estuaries.

“We’re updating our priorities,” Hanak explained, providing a long list that begins with changing climate, population growth, mandated groundwater sustainability, and an aging water grid based on hydrology.

WIFIA

Improving infrastructure is a national challenge, but EPA’s Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program has provided more than $3.5 billion in credit assistance to finance $8 billion for water projects, a spokesperson revealed.

Established in 2014, WIFIA is a federal loan and guarantee program administered by EPA. WIFIA’s goal is to accelerate investment in the nation’s water infrastructure by providing long-term, low-cost supplemental credit assistance for regionally and nationally significant projects.

A 2012 AWWA study indicated that the U.S. needs to invest $1 trillion in 25 years to maintain the level of service. “We’re behind the curve,” Holmes said. AWWA advocated for WIFIA in 2014 due to the recognized need for a larger program of low-cost loans. Funding began in 2017.

EPA recently invited 38 projects in 18 states to apply for WIFIA loans. If approved, EPA will loan $6 billion. “And since they fund only 49 percent of a project,” Holmes added, “that supports $12 billion in infrastructure investment.”

Of the selected projects, eight are water reuse or recycling projects, 11 will reduce lead or emerging drinking water contaminants, and 33 will address aging infrastructure.

Funding

Funding goes hand-in-hand with legislation. Holmes said WIFIA is well-funded. “Congress appropriated $60 million.”

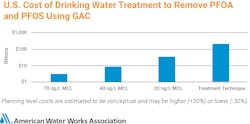

But, depending on how PFAS legislation is finalized, capital costs for treatment to remove PFOA and PFOS in drinking water could exceed $3 billion nationally, or $38 billion if federal implementation mirrored state levels (See Fig. 1). There is even potential that a treatment technique standard could be mandated at a cost of more than $370 billion in capital investment and $12 billion in annual costs.

The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee passed H.R. 1497, the Water Quality Protection and Job Creation Act of 2019. Among its benefits is the largest-ever increase in funding for the Clean Water SRF to enable communities to invest in addressing aging infrastructure and water quality challenges. In addition, the bill authorizes other clean water programs that offer financing to local communities and federal grants to municipalities for stormwater and sewer overflow. WW

*Editor’s Note: The NDAA was signed into law on Dec. 20, 2019.