Bipartisan legislation focuses on important risk management and operating details

America’s Water Infrastructure Act, also known as the Water Resources Development Act of 2018, was signed into law October 23, 2018, by President Donald Trump.

The 130-page Act is a rare bipartisan collaboration between House and Senate Democrats and Republicans to focus attention on the nation’s water infrastructure. The Act has garnered positive feedback from a diverse group of water industry associations such as the American Water Works Association (AWWA), the National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

This is an influential and ambitious law, and if you operate a water system or help those who do, take note. There is a strong focus on the role of the Army Corps of Engineers with respect to water resources development (Title I) and drinking water system improvement (Title II), as well as coverage of hydropower-related topics (Title III).

Here we’ll focus on the section affecting drinking water systems, from a business and utility (not legal) perspective.

Intractable Water Systems and System Consolidation

Section 2003 amends the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) to create a new focus on “intractable” water systems, defined as community or non-community water systems that serve a population less than 1,000 and have significant noncompliance histories.

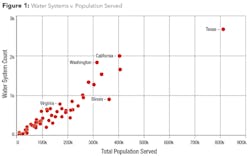

Research from FirmoGraphs, a business intelligence and data science firm specializing in the North American utility and industrial markets, indicates that there are approximately 32,000 water systems serving populations of 1,000 or less. The top five concentration of these systems are in Texas, California, Washington, New York, and North Carolina. A study to identify intractable systems will be completed within two years of enactment to identify the subset of these systems having difficulties providing potable water.

Smaller utilities may have a more difficult time managing treatment and distribution infrastructure. A 2018 Utah State University study found, for example, that smaller utilities have twice the water main breaks as larger utilities. Consolidations may also be inevitable as many states simply can’t effectively manage so many small systems and provide adequate inspections.

Section 2010 seems closely related, granting the authority to “require the owner or operator of a public water system to assess options for consolidation, or transfer of ownership of the system.” In other words, non-performing systems, irrespective of size, may be compelled to consolidate.

Lead Testing in Schools

In Section 2006, new SDWA requirements are added with respect to drinking water testing and fountain replacement in schools, including the provision of technical assistance. There are spending authorizations for testing and water fountain replacement with a focus on low-income areas.

Consumer Confidence Reports and Compliance Monitoring Data

Section 2008 updates requirements pertaining to Consumer Confidence Reports. For community water systems serving populations of 10,000 or more, the reporting frequency is changing from annual to at least biannual. This will impact more than 4,300 water systems. The top five impacted states (by concentration) are Texas, California, Florida, Illinois, and Massachusetts. There are also to-be-determined revisions to increase the quality and accuracy of the information presented.

Related Section 2011 requires the EPA to submit a strategic plan within a year to implement an electronic system for submitting and retrieving SDWA compliance data, by public water systems to the states, and the states to the EPA.

A combination of process modeling, data collection, process historian, process control, asset management, and IT security solutions promises to keep critical water treatment infrastructure operating effectively.

Risk and Resilience Assessments

Of substantial interest are changes respecting vulnerability assessments as outlined in Section 2013. All community water systems serving populations greater than 3,300 were required to perform vulnerability assessments. The scope is now expanded to include:

• Risks from malevolent acts, such as terrorism

• Risks from natural hazards, such as earthquake and flood

• Physical asset resilience, such as pipes and treatment facilities

• Electronic asset resilience, including computers and other automated systems

• Chemical handling and storage

• System operation and maintenance

We believe this will impact over 9,200 drinking water systems nationwide.

The addition of natural hazards and electronic assets is a substantial and important change from post-9/11 requirements. With respect to natural hazards, U.S. utilities have experienced substantial interruptions due to hurricane-related flooding and wildfires in recent years. Electronic asset resilience involves identifying cybersecurity threats, as outlined for example in AWWA’s recent Cybersecurity Guidance & Tool. Lacking the internal bandwidth or capabilities, many utilities may seek outside assistance to address these far-reaching risks.

Community water systems must self-certify compliance, with the deadline depending on the population served. Deadlines are:

• March 31, 2020, for systems serving more than 100,000

• December 31, 2020, for systems serving greater than 50,000 (and less than 100,000)

• June 30, 2021, for systems serving more than 3,300 (and less than 50,000)

Of note, it doesn’t appear that the plans need to be submitted, only the self-certification. Emergency response plans must also be prepared, no later than six months from the assessment dates discussed above, including the newly expanded requirements.

Authorizations and the Criticality of Appropriations

As always, although the Act authorizes many important expenditures, including grants for state programs, it is Congress that funds the various programs through appropriations. The devil will be in the details when it comes to funding of individual program areas.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produces cost estimates for bills and resolutions, and as of late November, a CBO Cost Estimate for this measure had not been received.

It seems likely that with both parties speaking favorably about infrastructure, and the President’s own stated commitment, that the Act would be suitably funded.

New SDWA requirements are added with respect to drinking water testing and fountain replacement in schools. It includes spending authorizations for testing and water fountain replacement with a focus on low-income areas.

Challenges and Opportunities

Water utilities and those serving them are seeking to derive the maximum value from capital assets. With the acceleration of aging and failing U.S. water infrastructure, the need to change and evolve has never been as crucial as it is today. Fortunately, there are many opportunities to apply cost-effective, higher-tech methods to what has traditionally been a conservative industry.

Utilities seeking to repair, replace, and protect water distribution systems have new options in addition to traditional “boots on the ground” methods to detect and repair leaks. These methods compliment, rather than replace, traditional methods. These can be infinitely more effective than an “operate until failure” strategy that may be prevalent, particularly in more leanly-resourced utilities.

Some new-market options for linear assets include, for example, solutions that can detect otherwise hidden leaks using radar-based satellite imagery. Both large and small utilities are reporting success, cost-efficiently identifying even smaller service line leaks using these methods.

Other options include the installation of permanent acoustic monitoring devices. The best deployments of these higher-tech options effectively pair the technology with the field crews to give the utility more “bang for the buck,” measured by leaks repaired per person per day, for example. Leak detection teams report initial skepticism, followed by strong support, of such new technologies.

There are also increasing deployments of newer-tech systems within treatment plants and pumping stations. A combination of process modeling, data collection, process historian, process control, asset management, and IT security solutions promises to keep critical water treatment infrastructure operating effectively.

Properly adapted, these types of evolving solutions may help smaller water systems offer reliable, compliant potable water to their customers, and keep them from becoming “intractable.” At its best, the Act may provide utilities, particularly smaller ones, with a framework to better operationalize asset management, protection, and resilience towards a more sustainable utility.

Conclusion

The passage of America’s Water Infrastructure Act into law was a surprise for many in the drinking water market, including utilities and the ecosystem of businesses that support them. For many, it is a pleasant surprise, with its bipartisan congressional support and attention to important risk management and operating details.

Every member of the water utility community has an important role to play in securing America’s water infrastructure. Utilities are increasingly regarding their customers as individuals with needs, habits, and strong opinions if things go wrong. With a combination of hard-working utility staff, governmental support, and evolving solutions, we have great reason to be optimistic.

About the Author: Dave Cox, P.E., is the founder and manager of FirmoGraphs LLC, a business intelligence and data science firm specializing in the North American utility and industrial markets, with a focus on analysis related to the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) of people, planet, and profit.

Resources

1. Folkman, S. Water Main Break Rates in the USA and Canada: A Comprehensive Study, Utah State University, March 2018.

2. America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018, S.3021, 115th Congress, 2018.

About the Author

Dave Cox, P.E.

Dave Cox, P.E., is the founder and manager of FirmoGraphs LLC, a business intelligence and data science firm specializing in the North American utility and industrial markets, with a focus on analysis related to the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) of people, planet, and profit.