A Sea Change In Water Infrastructure Funding

The Expanding Role of Private Investment in Public Infrastructure

By Angela Godwin

In February, after months of speculation, President Donald Trump released his long-awaited infrastructure plan or, as it’s more formally titled, his “Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America.”

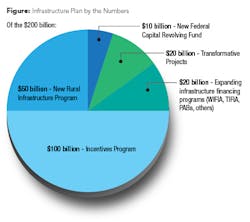

In a very concise nutshell, the plan aims to generate $1.5 trillion in new investment in infrastructure over ten years from a federal purse of $200 billion. A major facet of the plan is that it seeks to speed up the permitting process, aiming to get projects approved in two years or less.

With regard to water, specifically, the plan proposes applying the same regulatory requirements to both public and private water and wastewater utility systems in order to “provide a level playing field for all service providers.” Further, the plan calls for extending access to Clean Water State Revolving Funds (CWSRF) to privately owned systems (under current federal law, while Drinking Water SRF funds are available to private systems, CWSRF funds are typically not).

Another point of interest: the plan puts significant emphasis on the use of state and private sector money to fund water and wastewater infrastructure projects. It laments that “under current law, even when a state or private sector entity provides the majority of the funding for a project, a project must still obtain review and approval under the laws of any federal agency with jurisdiction.” This, it suggests, causes unnecessary delays, which in turn discourages private investors.

The plan recommends changing the law to provide more flexibility to projects that are being funded with primarily non-federal monies (i.e., de minimis federal share).

Expansion of the WIFIA program and the use of Private Activity Bonds (PABs) is outlined, as is the creation of an “Incentives Program” to encourage state, local, and private investments.

One thing that is not addressed in the 55-page infrastructure plan is the source of the $200 billion in federal funding. From Trump’s FY2019 budget request, also released in February, it would appear that much of it would come from cuts to other programs, such as regional water quality programs. Of those, the Great Lakes and Chesapeake Bay programs would be the only survivors, but not without very deep cuts. On a somewhat reassuring note, the Drinking Water and Clean Water SRF programs would remain funded at current levels.

Both the infrastructure plan and Trump’s proposed FY2019 budget request have long roads ahead of them. But private investment is a central component of both and one that water and wastewater utilities will need to consider as they continue to wrestle with aging systems and how to finance their repair.

Green Bonds

One avenue for tapping into private investment for municipal water and wastewater projects is through green bonds. According to Ted Chapman, senior director of the U.S. Public Finance Infrastructure Group with S&P Global Ratings, a green bond is typically “a municipal bond whose proceeds are going to be used for some sort of a mitigating circumstance, mitigating an environmental impact, or maybe improving resiliency or sustainability.” These would include objectives such as pollution prevention and control, protection of watersheds and coastal environments, sustainable drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, and adaptation to climate change.

It’s a broad definition that results in a certain amount of “self-labeling,” he acknowledged, but noted that guidelines do exist. The International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) has developed a set of four core Green Bond Principles (GBP) that has become a widely accepted yardstick for determining “greenness.”

“The first one, obviously, is the use of proceeds,” he said, “but also they look at how the projects were evaluated and selected in the first place.” The third component involves how the proceeds are managed, and the fourth principle is all about reporting and entities engaging in a continuing disclosure.

Regarding the U.S. market for green bonds, Chapman said he would characterize it as “very robust.” Recent research from S&P found that these mechanisms have grown exponentially over the last decade. “About 10 years ago, total market activity was about $500 million — and this includes everything, not just water and sewer utilities but all social infrastructure like energy efficient buildings, electric vehicles and so forth,” said Chapman. “In 2017, it was over $43 billion.”

That growth is expected to continue, he said. “There are certain investors with a particular risk appetite and strategy who love these things,” he noted. Some find the projects appealing, others are attracted by the issuers. “Some green issuers that have recently come out — like San Francisco Public Utilities Commission or N.Y. State Dorm Authority — are also very highly rated,” he said. Given that investors are generally interested in making sure their investment is repaid in full and in a timely manner, this is a major factor.

Case in point: DC Water began issuing green bonds in 2014 to raise capital for its DC Clean Rivers Project. It was a landmark transaction: Not only was it the utility’s first green bond, it was the first century bond issued by a water/wastewater utility in the U.S. and the first green bond to include a sustainability opinion from an independent second party.

Now when DC Water comes to market, they typically get oversubscribed multiple times, Chapman explained. “What I mean by that is, DC Water has two to three to four times as many interested investors as they do bonds.”

It’s Going to Be All Rate

Because DC Water is such an attractive investment, investors bid down the price with competing rates of return. “And DC Water just sits back and says, ‘Well great, this is improving the cost of borrowing,’” Chapman said. And it’s all because they are highly rated.

“S&P has a AAA rating on them,” said Chapman, “which is our highest rating. These are the kinds of benefits you can get when you can demonstrate strong financial integrity and strong operations.”

Doug Scott, a managing director in Fitch Ratings’ U.S. Public Finance Group, agreed. “We’re talking about the ability of a utility to repay its obligations in a full and timely manner,” he said. “It’s important because most utilities rely upon some sort of external financing in order to fund their capital programs. Credit ratings help investors to delineate the relative strength of the utility to continue to manage its business and generate revenues to repay its obligations.”

The key to credit-worthiness is two-fold, he noted: financial performance is obviously critical, but it’s also important to be able to sustain that performance over time. “Instead of being reactive to demands or costs as they arise,” said Scott, utilities need to “try to anticipate those and make sure their financial levels are in good shape.”

Know Thy Neighbor

That can be a bit complicated, especially when it comes to water supplies that cross borders. Fitch recently reported that water disputes that make it to the Supreme Court could have credit implications for the utilities involved, depending on the Court’s determination. “The issue with that is that, as populations continue to grow and as there are competing demands for the supplies that are out there, we’ve been seeing increasing pressures associated with water supplies and how those are divvied up,” Scott explained. “As a result, courts are having to get involved and having to take a more active role in settling these disputes.”

Two cases in particular are being closely watched: one is between Florida, Georgia, and Alabama; the other is between Texas and New Mexico.

According to Fitch Ratings, if the Supreme Court delivers a determination “that reduces or limits supplies to the municipalities, [it] could result in increased borrowings to finance development of additional supplies.” This, in turn, “would force utilities to manage between charging more for service and/or lower financial margins.” Because credit stability is affected by affordability and addressing deferred maintenance, if either (or both) of these conditions is compromised, it could impact the credit worthiness of the utilities involved.

The two cases noted above are high profile because they’ve made their way to the Supreme Court, but conflicts like these becoming more common. “As time goes by and there are more demands being placed upon supplies, the courts may have to take more of an active role in settling these disputes,” suggested Scott.

For water and wastewater utilities issuing public debt, credit worthiness is naturally a very important consideration. But it’s not the only funding mechanism that requires a credit rating. The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program requires one credit rating during the application process and a second when the loan is closed. It’s worth pointing out that in his infrastructure plan, President Trump is proposing eliminating the second rating opinion. “Opinion letters can be expensive and time intensive for borrowers to obtain,” the plan states. “Reducing [it] to allow for one opinion letter instead of two would reduce WIFIA borrowing costs for borrowers.”

Public-Private Partnerships

A public-private partnership (P3) is another way of leveraging private sector dollars for municipal projects. Under the right circumstances, a P3 can help a utility achieve a specific objective while simultaneously minimizing risk. But a P3 is not a one-size-fits-all approach. There are as many different kinds of partnerships as there are utilities, and it can make the landscape confusing.

“You may talk to two or three people about what a P3 is and they might all have slightly different views about it,” said Jeff Hughes, director of the Environmental Finance Center (EFC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For some, the word “private” implies privatization — which is, in most cases, not the same thing.

Typically, “a public-private partnership [is] where the private entity doesn’t own the assets but has taken on some of the financing responsibility and some of the risk through some creative transactions,” Hughes explained. “Whereas privatization is the model where a local government completely sells all its assets and then wouldn’t even be involved in running the utility; it would be run by a private company that owns private assets.”

Much like green bonds, P3s have traditionally seen faster adoption in the international market, but these unique alternative delivery models are gaining traction in the United States, particularly where a community government is faced with a financing challenge that, for whatever reason, it can’t deal with under the more traditional models. “Or, they are looking at a project that, with the traditional model, carries more risk than they are comfortable with,” Hughes explained.

Hughes and his team recently completed a study of nine communities that utilized a wide range of partnerships to achieve their goals. The research did not presume to classify these delivery models as successes or failures, but rather looked at the objectives, the promised financial impact, and (if the information was available) the actual financial outcomes.

One of the big takeaways, Hughes said, was having realistic expectations at the outset. “It may sound obvious but some of these get sold as providing all different types of benefits — even beyond what those on the private side would say that they could deliver,” he noted. “And so they sort of just expand.” Expectations become impractical, with participants thinking they’ll end up with lower costs, lower rates, better service, lower risk, et cetera. “And most of what we found is that you had to pick just one or two from that list — you couldn’t get all of them.”

Hughes said each of the nine case studies offered valuable insights. “They were so incredibly different in why they were done, the size, who got risk, who had authority to raise rates, and the terms.”

One of the case studies looked at the Bayonne, N.J., Water and Wastewater Concession Agreement, which has received a lot of positive attention in the press. It was a concession agreement between the Bayonne Municipal Utilities Authority and Bayonne Water Joint Venture (a partnership between Suez/United Water and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts).

“That is one of the ones that corrected a legacy of underinvestment,” Hughes explained, “so by most accounts, the level of service and the investment in assets are much higher now under the P3 model.”

Hughes noted the project’s emphasis on performance. “It took a lot of things that everybody agreed needed to be done and put them into an enforceable contract. And that seemed to have provided ironically the most benefit there.” As a result, Hughes said, Bayonne “ended up with this neat model where it’s all projected into the future, where they know how much they are going to invest every year.” The rate increases are built in, he explained, “so it’s not as much of a political decision to increase rates.”

Conclusion

Funding needs for water and wastewater infrastructure dwarf what’s available through traditional federal sources. Private investment is another tool in the utility’s funding toolbox, and one that, if Trump’s budget proposal and infrastructure plan come to fruition, may begin to play a more prominent role than ever before. WW

Editor’s Note: The case studies researched by EFC offer valuable insights to utilities considering a P3. They are available online at https://efc.sog.unc.edu.

About the Author: Angela Godwin is chief editor of WaterWorld and Industrial WaterWorld magazines. She can be contacted at [email protected].

About the Author

Angela Godwin

Editorial Director

Angela Godwin is the previous editorial director for Endeavor Business Media's Process/Water Group.