Looking Underground

How groundwater modeling can help you understand your underground resources

By Jim Finegan

Groundwater can be a challenge for municipalities and other government entities that are developing water treatment and distribution systems, as well as sewerage systems.

Different locales present different challenges and opportunities, and agencies must be prepared to respond to all groundwater eventualities. With rising waters facing many areas, and others subject to drought, it’s more important than ever to understand what types of water resources and challenges are presented beneath any type of development or municipal water resources site.

The problem is that there are no cookie cutter solutions. Each development, each location, each community poses its own unique challenges. For instance, in areas where rising waters — both inland and coastal waters — are problematic, they can make development difficult by leaving sites susceptible to flooding. Conversely, in areas that are susceptible to drought, developing agencies face much different challenges because there must be sufficient supply to support new development.

The questions facing agencies in both situations are: how can you know what’s below before you commit to a development or begin work, and what might happen to groundwater conditions in the future?Groundwater Modeling

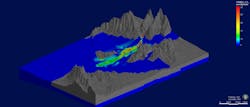

The answer may be found in computer-based groundwater modeling, which can provide answers to questions about the subsurface environment. Modeling may provide the answers that developing agencies need to support their business and resource decisions.

A groundwater model utilizes a mathematical analog to simulate the physical and chemical processes affecting the movement and quality of groundwater.

The process begins with the drilling of boreholes. Instruments are inserted into the holes to collect the data on which the model will be built and the data is translated into computer code that allows scientists and engineers to simulate the natural condition below ground. In essence, the scientists and engineers will use the computer code to “view” what’s underground and the resultant model should be able to predict how water flows underground. The trick is to select a model that will best match the known conditions underground without including more detail than needed. By using equations that simulate groundwater flow, run multiple times throughout the process, and estimating hydrogeological conditions, as well as soil characteristics, scientists and engineers can deduce the flow and quality of the water below.

Groundwater modeling begins with the development of a conceptual site model (CSM), which provides an abstract set of physical boundaries to define groundwater flow and variables that can affect the rate, direction, and quality of the groundwater within the area defined by the CSM. The CSM should be developed prior to the development of a groundwater model, and both the CSM and the groundwater model should be continually updated and refined as new data are collected and analyzed.

But what water supply and groundwater remediation decisions require quantification? The answer is that nearly all decisions require some level of quantification. The question is which models are right for which situations?

Choosing the Right Model

There are two basic categories of models, groundwater flow models and groundwater fate and transport models, with a number of examples in each category. Flow models only explicitly account for groundwater (and sometimes surface water), while fate and transport models evaluate groundwater and allow chemical migration — including chemicals that have dissolved in the water or sorbed to aquifer materials — to be simulated.

Groundwater flow models are used to simulate the volume, rate, and direction of groundwater movement within the subsurface. A groundwater flow model requires a thorough understanding of the hydrogeologic system inputs (such as natural and artificial recharge, groundwater flow, and leakage from surface waters) and outputs (i.e., evapotranspiration, under flow, loss to surface waters, and pumping) as well as site-specific information on aquifer properties.

Groundwater fate and transport models simulate the movement and chemical alteration of contaminants as they move through the subsurface. They may be used to model contaminants in both the groundwater and vadose (unsaturated) zones. Fate and transport models used to model transport within a groundwater zone require the development of a calibrated flow model or, at a minimum, an accurate determination of the flow velocity, which has been based on field data.

When determining which model to utilize, the key consideration is what type of decision is being made. Development of a fully three-dimensional groundwater flow and transport model for the sole purpose of evaluating groundwater may be overkill. It’s often more appropriate to rely on less labor-intensive methods. Conversely, it is generally not appropriate to rely solely on simple analytical equations for projects involving complex sites, such as areas where geochemically complex contaminant plumes have commingled. In such complex cases, the project may require some preliminary or screening-level modeling prior to deciding what outcomes might be expected.

The choice of model is typically influenced by the purpose of the study and the scale of the study site, such as the detail needed to represent the hydrogeologic processes to be evaluated and the acceptable uncertainty in modeling results. For example, assessing hydraulic capture with multiple extraction wells may require either an analytic element model or a numerical model, but chemical fate-and-transport modeling is not needed and an analytical solution may be too simple to address superposition (i.e., the combined drawdown from more than one pumping well).

Specific model codes and modules/packages as well as the need for other features, such as a linked vs. fully-integrated model that also includes surface water, are selected following determination of model type.

These are often difficult questions to answer because there are so many different models and packages to choose from, and the process typically requires a trained groundwater modeling expert to manage.

X-Ray Specs

Water treatment and distribution systems and sewerage systems are complex, requiring specialized engineering, architectural, and planning expertise to complete. Understandably, because of the complexity of these buildings and systems, most of the designers’ attention is focused above the ground. However, the geology below ground is just as important; having too much or too little water below the surface can have a significant impact on the success of any development. Groundwater modeling can help developing agencies and their engineering team analyze the flow and quality of the water that lies below the surface before the project begins. This is invaluable information, but it’s important to choose the right type of model. WW

About the Author: Dr. Jim Finegan is a California-certified hydrogeologist who leads Kleinfelder’s groundwater modeling practice. He can be reached at [email protected].