Bacteria bullets target toxic algae

DELAWARE, OCT 10, 2019 -- Communities across the United States and around the world, along salty bays to freshwater lakes, increasingly are grappling with the dangerous effects of microscopic algae that suddenly grow out of control in these waters. This dramatic growth may be triggered by storms, a glut of nutrients, rising temperatures and potentially other factors.

Called harmful algal blooms (HABs), these massive events can produce toxins that sicken people, marine mammals, fish and birds, sometimes even resulting in death. Local economies dependent on tourism, clean beaches and healthy fisheries also suffer losses.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), HABs are a growing problem in every U.S. coastal and Great Lakes state. Red tides, in particular, have plagued Texas and Florida’s Gulf Coast and additional forecasting programs are in development for other HAB hotspots including Lake Erie, Puget Sound, Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Maine.

But now some of the most harmful algae — those that produce red tides — may finally have met their match. At the University of Delaware, researchers have invented an application to keep these toxic organisms in check, and without harming other sea life. UD marine scientist Kathryn Coyne, who led the work, calls the invention a “magic bullet” for red tide, and it is indeed small, yet powerful.

“We have been working with a bacteria that produces a compound that can kill dinoflagellates, which are among the most noxious of harmful algal bloom species,” said Coyne, who is an associate professor of marine biosciences in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment, and director of the Delaware Sea Grant program. “We believe this natural algicide, embedded in gel beads and deployed in areas at risk, can prevent red tides from occurring or shut down those underway.”

Tamping down a toxic microbe

Dinoflagellates are microorganisms with two tails, or flagella, that help them motor around in coastal waters in a spiraling motion. While they are food for many marine life, a few species are notorious for “blooming,” or reproducing in such great numbers, that they color coastal waters brownish red, hence the name “red tide.”

During a bloom, these dinoflagellates can release poisons including neurotoxins that get boosted into the air by breaking waves, causing respiratory distress in people and wildlife nearby. Other dinoflagellate toxins accumulate in fish and shellfish, sickening people and animals who eat them. Paralytic shellfish poisoning, for example, may result in numbness of the face and neck, difficulty swallowing, loss of speech, and in rare instances, complete paralysis and death.

What can stop this toxic microbe? Another microbe. Coyne and UD collaborator Mark Warner and their research labs discovered a few years ago that Shewanella, a common inhabitant of coastal waters — capsule-shaped just like your favorite pain reliever — secretes a compound that is lethal to dinoflagellates.

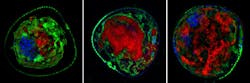

“In effect, the compound induces programmed cell death, causing the dinoflagellates to commit cellular suicide,” Coyne said.

In this process, also known as apoptosis, enzymes methodically break down and destroy the cell nucleus like a ball of yarn coming unraveled.

It was important to the team that the bacterial compound impact only dinoflagellates and not other members of the ecosystem. In NOAA-funded research, Coyne and Warner and fellow marine scientists Tim Targett and Jon Cohen and their teams ran test after test and found that the algicide did not have a negative effect on fish or shellfish or on other types of algae, for that matter.

“This was important. Algae are primary producers, and a lot of other organisms rely on them as a source of food,” Coyne said. “We needed to make sure that the algicide did not kill other species of algae in the water.”

Making bacteria bullets

Coyne is now exploring different options for how the algicide could be deployed in the environment. In a recent Delaware Sea Grant project, she and doctoral student Yanfei Wang discovered that Shewanella can attach to and live within porous materials. Thus, the duo decided on a simple approach: Embed the bacteria in gel-like alginate beads. Package the bullet-like beads in mesh bags, which could be set out in coastal waters where needed to prevent or mitigate a bloom. Then retrieve when the job is done.

“Embedding the bacteria in these gel-like beads and putting them back into the water in higher concentration is considered an environmentally neutral approach rather than simply going out and spreading the bacteria,” Coyne said of the patented technique. “By having the bacteria in higher density in these beads, they’re still secreting the algicidal compounds that target the dinoflagellate almost like a magic bullet, and could be deployed or removed as needed.”

Coyne, who also holds a patent on using algae to remove nitric oxide from industrial flue gas emissions, praised personnel in UD’s Office of Economic Innovation and Partnerships (OEIP) for their advice and assistance with her efforts to create this latest invention.

“It feels great to be an inventor and to have developed an application that will really do some good to mitigate or prevent these harmful algal blooms,” Coyne said.

“As a young scientist, you want to solve a real problem,” Wang added. “You ask yourself, ‘What can my research do to help the world?’ So this has been very exciting and thrilling for me.”

The invention already has stimulated commercial interest and OEIP is in discussions with companies engaged in the water industry.

Source: University of Delaware