The Great Wall, Mark II: Engineering China's Water Lifeline

Totalling a century from conception to completion, costing over $60 billion, China's South-North Water Transfer Project will be one of the greatest engineering feats of the modern era. In October the central route of the world's most expensive water supply system was complete but at what environmental and economic price?

By Tom Freyberg

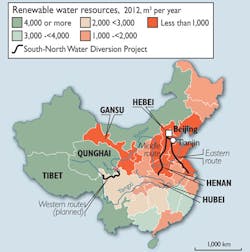

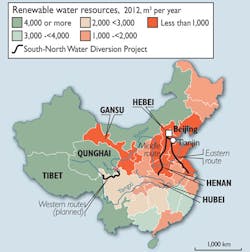

Revered and criticised in equal measure, Mao Zedong – otherwise known as Chairman Mao and the founding father of modern China, could be a called, among many things, a visionary. It was in 1952 when Mao realised his country faced a major stumbling block: the North is responsible for the majority of industrial and agricultural activity, yet lacks the much needed water that lies in the south.

As a result, the contrast between the arid North, the cradle of Chinese civilisation, and the water-abundant South has induced many waves of migration over the last three millennia.

Furthermore, groundwater supplies have been heavily exploited in the North. Up to 35% of the North's aquifers are used compared to 6% in the South.

"They're effectively mining down the groundwater," says Simon Spooner, consultant at Atkins Water & Environment International and honorary professor at Nottingham University Ningbo, China. "In the Hai river basin around Beijing they are using more than 100% of total water resources that are available. You've got a desperate situation. The government has had to do something about this – otherwise Beijing will run out of water and a lot of the cities will have serious problems and will not be able to grow. It will cause a crisis."

The solution

Even though it was 60 years ago, Mao predicted that the North-South divide and struggle for water resources would get worse. Taking inspiration from his predecessor, Sun Yat-sen – a Chinese revolutionary, first president and the founding father of Republic of China, Mao had an idea. The North would "borrow" water from the South, or to transfer it.

Officially known as the South-North Water Transfer (SNWT), the plan was to build over 2,500 km of canals and pipelines to shift water from the south to the north and divert water where needed by Eastern, Central and Western Routes. And after 50 years of much deliberation, debate and discussions, it was in 2002 when this ambitious plan was approved.

The initial Eastern Route was completed in 2013. This involved deepening and broadening the existing Grand Canal, built some 1400 years ago to take 14.8 billion cubic metres of water a year more than 1,000 km north from the Yangzi River towards the city of Tianjin. Although initially, due to contamination, the water at the end of this route wasn't quite as clean as where it started.

"It's quite an achievement to reuse ancient architecture," adds Spooner. "However, the canal had become a sewer so more money spent on sewage treatment, in order to make sure this water was usable at the other end than on the actually construction costs of the scheme. They knew this in advance. It's not as though they extended the canal and then found the water couldn't be used."

Fast forward 12 years and at the end of October 2014, the second arm of the SNWT- known as the Central Route - was completed. Stretching over 1200 km northward (see box out on project details), the central part of the ambitious project was under construction for 11 years.

As a result, around 500,000 m3/day of water will flow from the Yangtze River to Beijing with estimates suggesting this could meet the demand of five million residents. Five water storage plants have been constructed to serve the Central Route of the water diversion project.

Environmental and social price

Originally thought to cost between $9 billion and $15 billion, current estimates now put the total project at $62 billion. However the "real" cost, when everything is complete, is predicted to be nearer $70 billion. Reliant on water for future growth in the North, it's clear the Chinese government is willing to stump up the cash to push SNWT through to completion, no matter what the cost or time it will take.

"This is a controversial issue as the cost of implementing the project has skyrocketed since it was first envisioned in 1950s," says Professor Niv Horesh, director of the China Policy Institute, University of Nottingham…"Ultimately, however, the project's viability can only be judged 50 years down the track when effects on population dispersion and soil subsiding due to over-drilling (funnel effect) are better measured against the staggering financial cost of construction."

Others say that the transfer could reverse China's dilemma: drying up the water-abundant South while quenching the parched North.

Professor Asit Biswas, founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management, was invited by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in the mid 1980s to advise the government on the project.

Speaking to WWi, he says: "Not only China but also in India and Brazil, when people do water transfers, they seldom consider steady increase in water requirements in water exporting regions. It is the same problem in Chang Jiang (Yangtze), Ganga and Sao Francisco. Water requirements in the exporting region are steadily increasing. Thus, in a decade or so this Chinese project will have difficulty in delivering the amount of water it is supposed to bring to Tianjin and Beijing."

Scott Moore, International Affairs Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations from the US echoes these thoughts: "There's a growing concern that by pumping quantities of water north, the central route will contribute to or will exacerbate water scarcity in the exporting region, particularly in the Han River basin, which is already quite water stressed."

Yet in October reports suggested there is a far bigger cost taking its toll on the country. Around 330,000 people have been resettled (a diplomatic word for moved) to make way for the project, with local estimates putting this number at nearer half a million.

Spooner believes associated media coverage has been blown out of proportion.

"While never easy for those concerned I think the problems of resettlement have been played up in the press," he says. "This sort of resettlement goes on all the time in China. It's constant. They're transforming their entire society. You've got tens of millions of people a year moving from the country to the cities.

"This requires having to build new urban infrastructure, accommodation and to reorganise the villages. It's probably the biggest migration in human history that is going on in China right now."

Tackling demand in China's mega cities

The migration of residents from rural to urban habitats will mean China's cities will host millions of additional residents , putting additional strain on water supplies. Playing host to over 20 million people, Beijing will be one of the off-takers from the Central Route.

Debra Tan, director of China Water Risk, argues that the South-North project is "by no means the magic-bullet solution". She says it's "only one of the ways to increase water supply in the North" and that "in Beijing SNWT is expected to eventually provide only around 25% of water use".

Meanwhile Spooner argues it is the rise of China's new megacities that will be reliant upon the transfer project.

"It's not just about Beijing by any means - only a little bit of the water goes as far as Beijing," he says. "The SNWT supplies many fast growing cities along the way as well. For cities like Zhengzhou, Handan and Shijiazhuang, would not be able to undertake the development plans that they have in place without the South-North transfer."

Shifting billions of cubic metres of water throughout the country addresses the challenge of supply but critics have questioned whether this actually tackles the heart of the problem: high water use. As Moore says: "Basically you're augmenting the supply rather than trying and do anything about the demand."

As well as the transfer project, China Water Risk argues that other options such as "recyclable potable water, rainwater harvesting and desalination must be and are indeed considered".

In an attempt to curb this demand, municipal and agricultural water consumption have been addressed by the Chinese authorities. In May 2014, Beijing increased the price of its drinking water for residents. The price rose from RMB4/m3 ($0.65) to RMB5/m3 ($0.81).

Also in 2014, China's State Council issued plans to save 26 billion cubic metres of water per annum from agriculture through improving irrigation efficiency and expanding irrigated land.

"Aside from the usual suspects of water diversion, desalination and water reuse and recycling, China will look for water savings from industry and agriculture," says Tan. "At over 60% of total water use, savings from agriculture are a must. Since around two-thirds of the China's arable land lie in the parched North, this makes sense."

Impact on desalination It was in February 2012 when China's State Council announced its 12th Five-Year-Plan for desalination. This set out a higher than expected target of 2.2 - 2.6 million m3/day of online capacity by 2015, versus less than 1 million m3/day.

With billions of cubic metres of water being transferred North, what impact is this having on China's desalination build out, once considered a major attraction for international companies?

"If you're just looking at it economically, then maybe the case is fairly close between them [desalination and SNWT)," says Spooner. "When you consider the energy requirement of desalination and the problems in supplying that energy, in terms of resource consumption and carbon emissions, then that's really looking quite problematic. The whole Chinese desalination journey seems to be getting a bit shaky as well. Some of the plants that have already been built have got problems they are looking into."

For others, the transfer project could not come soon enough. "The South-North transfer project will improve distribution and availability [of water] across China," says Zhang Zhenpeng, managing director of Beijing Enterprise Water Group (BEWG) International.

Future proofing China

Attempts to curb high water use and effect on domestic desalination capacity to one side, it's clear the SNWT is needed in a country which has grown at an unprecedented rate. Through engineering, physically diverting water from where nature intended it to be to where humans need it to be, China is preparing for the future. To overtake the US as the world's number one superpower, additional water supplies are needed.

Professor Biswas believes SNWT will only be one measure among a suite of issues that need to be addressed.

"As I told Deng [former Chinese leader], the main problem in China is poor water management," he says.

"The South-North water transfer will buy them time for about 10-15 years, and then they will have to consider water pricing, institutional reforms, extensive reuse and recycling, etc., to radically improve water management practices. The current plan is to reduce agricultural water use by 30% within a decade. This is doable."

Meanwhile Spooner believes getting a project of this monumental scale wrong is not an option.

"It's critical to them being able to carry on with the development model that they have," he adds. "If they get it [SNWT] wrong, they will have food shortages and internal security problems. There's going to be a lot of people for whom this will be the greatest thing that's ever happened – it's freed them from a very limited and poor existence but that doesn't make very good headline news in the West."

He adds: "The transfer of water will not solve the problems on its own. It has to happen hand in hand with water saving and demand management – and that is the plan – for new resource efficient cities and the reform of water use in agriculture."

Unlike many Chinese projects that are completed quickly and on budget, the Central Route was significantly behind schedule and has big cost overruns. But then this is no ordinary project.

Chairman Mao once observed: "The South has plenty of water and the North lacks it. So if possible, why not borrow some?"

Over 60 years later, as Mao's (and ultimately Sun Yat-Sen's) idea slowly comes to fruition with the North indeed "borrowing" water from the South, the country could soon be thankful for what will be the country's necessary lifeline for continued growth.

Tom Freyberg is chief editor of WWi magazine. For more information on the article, email: [email protected].

Project details: East to West Routes

Eastern Route: 1,156 km long, moves 14.8 billion cubic meters of water a year, To: Tianjin region. From: Southern portion of the Yangtze River.

Central Route: 1,267 km long, moves 13 billion cubic meter of water a year. To: Beijing and others. From: The Danjiangkou Reservoir on Han River.

Western Route: 500 km long (noncontinuous), moves 8 billion cubic meters of water a year, From: Three tributaries of Yangtze River, (near Bayankala Mountain). To: Qinghai, Gansu, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Hui (semi-autonomous) provinces. Still in design and not yet operational.

More Water & WasteWater International Archives Issue Articles