Saudi researchers produce drinking water from dusty desert air

SOURCE: KING ABDULLAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY (KAUST)

SAUDI ARABIA, DEC 5, 2018 -- A simple device that can capture its own weight in water from fresh air and then release that water when warmed by sunlight could provide a secure new source of drinking water in remote arid regions, new research from KAUST suggests.

Globally, Earth's air contains almost 13 trillion tons of water, a vast renewable reservoir of clean drinking water. Trials of many materials and devices developed to tap this water source have shown each to be either too inefficient, expensive or complex for practical use. A prototype device developed by Peng Wang from the Water Desalination and Reuse Center and his team could finally change that.

At the heart of the device is the cheap, stable, nontoxic salt, calcium chloride. This deliquescent salt has such a high affinity for water that it will absorb so much vapor from the surrounding air that eventually a pool of liquid forms, says Renyuan Li, a Ph.D. student in Wang's team. "The deliquescent salt can dissolve itself by absorbing moisture from air," he says.

Calcium chloride has great water-harvesting potential, but the fact it turns from a solid to a salty liquid after absorbing water has been a major hurdle for its use as a water capture device, says Li. "Systems that use liquid sorbents are very complicated," he says. To overcome the problem, the researchers incorporated the salt into a polymer called a hydrogel, which can hold a large volume of water while remaining a solid. They also added a small amount of carbon nanotubes, 0.42 percent by weight, to ensure the captured water vapor could be released. Carbon nanotubes very efficiently absorb sunlight and convert the captured energy into heat.

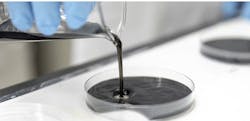

Renyuan Li pours the hydrogel into a petri dish and allows it to form to the mold. © 2018 KAUST

The team incorporated 35 grams of this material into a simple prototype device. Left outside overnight, it captured 37 grams of water on a night when the relative humidity was around 60 percent. The following day, after 2.5 hours of natural sunlight irradiation, most of the sorbed water was released and collected inside the device.

"The hydrogel's most notable aspects are its high performance and low cost," says Li. If the prototype were scaled up to produce 3 liters of water per day--the minimum water requirement for an adult--the material cost of the adsorbent hydrogel would be as low as half a cent per day.

The next step will be to fine tune the absorbent hydrogel so that it releases harvested water continuously rather than in batches, Wang says.