Study examines influence of soil structure on US water resources

LAWRENCE, KS, SEPT 24, 2018 -- According to a University of Kansas study, evidence suggests structural changes to soil is happening faster than previously thought, altering water quality and availability throughout the U.S.

"Water resources are governed by properties of the soil just beneath the Earth's surface," said Pamela Sullivan, assistant professor of geography and atmospheric science at the University of Kansas. "For a long time, we thought properties of these soils are changing at a slow rate. But a lot of evidence is coming to light that they're responding to climate change and different kinds of land use more quickly. They're responding quickly because biota in the soil are responding -- both plants and microbes -- and as they do, they're changing properties of soil. But we don't have good measurements of how that happens or the ability to put into models the interactions and feedbacks that will determine water resources in the future."

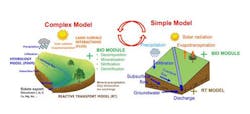

Sullivan is leading work under a $738,562 grant from the National Science Foundation to develop new mathematical models to analyze causes of these observed alterations in soil structure -- the arrangement of soil particles and pores -- and to examine plant-soil-water responses to varying environmental conditions.

"This work looks at both the biogeochemistry of the soil and how it changes the soil structure," Sullivan said. "Anyone who cares about what water resources will be like in the future will care about this. Projections and management decisions and understanding of flood dynamics can be influenced by the structure of the soil. If we don't understand that, we won't do a good job of understanding how it influences water."

The KU researcher said the relationship between soil and water was defined by the soil's matrix of minerals and organic matter and the spaces between, called porosity. These properties are undergoing changes that the new NSF grant will examine by sifting vast amounts of data.

"Changes in precipitation patterns are driving changes in the system itself," Sullivan said. "It changes the way organic carbon cycles through the system. The structure changes to favor infiltration of water or favor runoff — water running over the land surface. The more overland flow we have, that comes with more erosion and bigger flood events."

Sharon Billings, KU professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and senior scientist with the Kansas Biological Survey, is a co-primary investigator. Daniel Hirmas, formerly at KU and now at the University of California Riverside, Li Li of Pennsylvania State University and Alejandro Flores of Boise State University are also co-investigators.

The grant work will fund four postdoctoral scholars and the training of 10 undergraduate researchers who will help develop a new suite of models to include biological, physical and chemical interactions from local soils in the U.S.

Learn more at news.ku.edu.