Sustainable groundwater use could lower agricultural poduction

In the U.S., 52 percent of irrigated land is used for corn, soybean and winter wheat production. The water used for irrigation is often unsustainably pumped groundwater. According to a recent Dartmouth-led study published in Earth’s Future, using groundwater sustainably for agriculture in the U.S. could dramatically reduce the production of corn, soybean and winter wheat.

Irrigation relies on extracting groundwater from aquifers, which also serve as a source of drinking water and are essential to lakes, rivers, and ecosystems. Aquifers are naturally recharged, as rainfall, snowmelt and other water infiltrate the soil, and are collected in a porous layer underground. If groundwater use, however, exceeds aquifer recharge rates, this reduces the amount of groundwater that is available in the aquifer, including for growing crops.

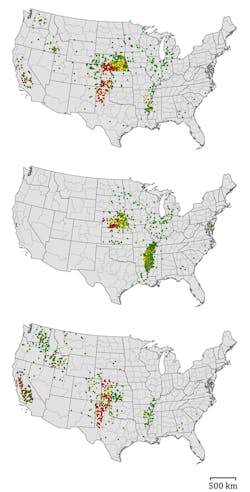

To analyze the impacts of sustainable groundwater use for irrigated corn, soybean, and winter wheat, researchers used a crop model to simulate irrigated agriculture from 2008 to 2012. The crop model uses information about daily weather, soil properties, farm management, and crop varieties, and was compared to survey data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to confirm its accuracy.

“Our findings underscore how corn, soybean, and winter wheat production could be affected if we chose to stop depleting aquifers across the United States,” says co-lead author Jonathan Winter, an associate professor of geography and principal investigator of the Applied Hydroclimatology Group at Dartmouth. “However, future precipitation, which affects groundwater resources, is difficult to predict, and improved irrigation technology, more water-efficient crops, and better agricultural water management could reduce the production losses from a transition to sustainable groundwater use.”

The findings show that Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas, which rely on groundwater from the High Plains Aquifer (also known as the Ogallala Aquifer) to grow these crops, would experience some of the greatest production losses as a result of sustainable groundwater use. This region is particularly vulnerable due to its lack of rainfall, which limits rainfed agriculture and groundwater recharge. Prior research found that the High Plains extracts three times as much groundwater as its aquifer’s recharge rate.

Central California, which relies on the Central Valley Aquifer, would also have large production losses in corn and winter wheat from sustainable groundwater use, but production losses of corn and winter wheat in California are limited due to the dominance of specialty crops, such as almonds, grapes, and lettuce, which limit the amount of land used to grow corn or winter wheat.

In contrast, the Mississippi Valley, a significant corn and soybean region, would experience relatively few production losses, as groundwater extraction is typically less than recharge over the region. The Midwest would also experience minimal corn and soybean production losses because the region is humid and relies mainly on rain-fed rather than irrigated agriculture.

“Sustainable groundwater use is critical to maintaining irrigated agricultural production, especially in a global food system that is already taxed by climate change, population growth, and shifting dietary demands,” says co-lead author Jose R. Lopez, a former postdoctoral researcher in geography at Dartmouth. “We need to expand the implementation of water conservation strategies and technologies we have and develop more tools that can stabilize the nation's groundwater supply while preserving crop yields and farmer livelihoods.”