Homeowners rarely think about it, but a catastrophic water leak could rearrange their lives at any moment. Maybe a pipe freezes. Maybe the slowly rusting water heater finally ruptures. Regardless of the source, the sudden opening lets municipal water rush free until the homeowner returns. It could be hours after the disaster began, and more than long enough for the broken pipe to turn a basement into a soup of ruined valuables and lost memories.

But modern water utilities can stop emergencies like this before they turn into a disaster. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) and a working knowledge of the Internet of Things (IoT) can spot spikes in usage and immediately alert the resident to take action.

But few utilities have this kind of technical knowledge on staff. That’s where third-party providers come in.

Badger Meter, for example, provides water utilities with the consumer-focused EyeOnWater smartphone application that can save thousands of dollars in property damage if and when a pipe fails.

“If the data suspects a leak at a property, through their registration and through their settings, they can say ‘please tell me if I have a leak at a property,'” says John Fillinger, director of marketing at Badger Meter. “They can then move forward and address the situation.”

While a life-saver in the event of a catastrophic failure, Badger Meter’s app can also help customers spot and address smaller leaks to save them money and long-term headaches. Fewer leaks translate to less demand for water.

Apps like this represent only the most visible benefit of AMI and the IoT. Used properly, these systems can help utility customers understand their water bills, help utility managers prioritize repairs, and even help maintenance crews make on-the-spot decisions in the field.

But, first, water utilities have to upgrade.

Badger Meter’s EyeOnWater smartphone application

HOW FAR WE’VE COME

Not long ago, water department employees had to visit each customer’s home to read the meter. The data collected in those days lacked both precision and detail, and allowed the utility to do little more than issue a bill.

Third-party providers later introduced meters equipped with short-range radio transmitters. This lets utility workers drive through the service area and lets a receiver in the back of the truck do the hard work of reading the meters.

Now, companies like Master Meter and Badger Meter sell fixed network meters that beam meter readings back to a central system as often as every 15 minutes. That granularity improves utilities’ visibility into their own systems and allows them to see the sudden spikes that might signal catastrophic failures.

“[With] drive by, you can detect the leak quickly at the meter; however, the utility won’t actually get notified for 30 days,” says Tim Schwartz, AMI product manager for Master Meter.

At present, the infrastructure to read meters on a 15-minute cycle challenges the budgets of many utilities in smaller municipalities. Using a public network, like the towers your cell phone connects to, costs too much.

“You can’t profitably run a product and maintain it on a cellular network today,” says Schwartz, “which is why all of the Water AMI systems on the market today are still proprietary communication protocols.”

Proprietary systems come with a lower day-to-day cost, but require a large upfront investment—which many utilities can’t justify. That, Schwartz says, is why his company has worked with Silver Spring Networks, a third-party provider that uses connected IoT devices to create a “mesh” network to connect devices.

Mesh networks use the devices attached to them to increase the network’s reach. Each new meter acts as a node that other meters can relay data through.

Silver Spring’s network also reaches beyond water meters. The company’s customers include electric utilities, gas utilities, and municipalities who use Silver Spring’s smart streetlight grid. Each of these devices works together. Smart streetlights relay data for smart water meters, and vice versa.

Master Meter’s partnership with Silver Spring, Schwartz says, lets the company sell advanced meters to utilities without the utility needing to build an AMI network covering the same geography or pay hefty fees to cellular providers like Verizon. Already, Schwartz says, Silver Spring covers more than 20 million advanced metering units, and that could double or triple in the next decade.

Even this solution may be out of reach for many municipal budgets. But, Schwartz says, “as these public networks grow, as the footprint gets larger and larger, it’ll be easier for more utilities to hop onto these networks.”

CUSTOMER SERVICE

Water utilities may never perform a better action of customer service than saving a customer’s home from a broken pipe, but AMI can also ease mundane customer service interactions.

Many of the water utilities that Badger Meter works with, Fillinger says, have integrated granular readings into the data seen by customer service agents. This can quickly defuse many complaints about water bills. When a customer calls a utility upset that their bill is higher than it should be, the customer service agent can see the client’s full history. If the on-screen chart shows a spike, the customer service agent can ask if the customer filled his swimming pool that day.

“In a lot of cases, people forget things that aren’t in the recent past,” says Fillinger. Diplomatically pointing out the customer’s error, he added, often defuses an angry rant before it starts.

AMI-equipped water utilities can also go a step further and prevent the call from ever coming in. Lance Brown, vice president of customer engagement for Smart Utility Systems (SUS), says many of SUS’s clients have created mobile and online platforms that give utility customers direct visibility into their own water usage.

“[As a customer], I can open the app, explore my usage data, drill down to a 15-minute detail and then pay my bill on my phone,” says Brown. “So the utility sees a little back office reduction while the customer gets a lot more information.”

This model, Brown noted, can answer many customer service questions without requiring expensive human-to-human interaction. It also follows the prevailing trend among the business community.

Consumers “[are] starting to use utilities like they use online banking,” says Brown.

Brown says SUS has also helped water utilities take a page from the playbook of cellular phone companies by using warning texts. Customers of SUS-partnered utilities can set a water budget for themselves, and ask to receive a text if they approach it.

Customer service measures like this, noted Jennifer Espelien, marketing manager for SUS, can be particularly important for areas with stringent water use regulations—like the entire state of California.

Under the strain of drought, California water utilities are doing everything they can to reduce water usage. Espelien and her team at SUS, she says, use social media and digital communications to spread water conservation tips. SUS gives water utilities the tools to see which customers are interested in information through which media, and then feed it to them at the right time, in the right way.

“It’s an opportunity to reach the person in the right manner and hopefully change their behavior,” says Espelien.

SUS can also help water utilities nudge customer behavior in more subtle ways. Brown noted that his local water utility includes a note telling him how well he conserves water compared to water customers with similar demographics.

“We’re in the top 20% of water savers,” says Brown. If he slipped to the top 30% of water savers, he might redouble his personal conservation efforts.

These clever new communications, he notes, represent a significant advancement for water utilities across the country. “Historically, utilities have not communicated well at all,” adds Brown.

Before transitioning to his role at Smart Utility Systems, Brown worked on the utility side. In his earliest days utilities struggled with customer data. A water utility with the correct phone number for 30 or 40% of its customers, he says, would be ahead of the pack.

Water utilities have put those days behind them. Drought-driven regulatory pressure has combined with a desire for enhanced customer service interfaces to push water utilities forward.

“In most of the responses that we’re seeing from utilities,” says Fillinger, “they’re all asking how best they can improve customer service.”

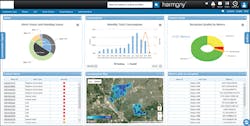

Master Meter’s Harmony water meter data management software

OPTIMIZING UPKEEP

Pipes, pumps, and meters all suffer from limited lifespans. Water utilities struggle daily to prioritize which parts of their infrastructure to upgrade or repair, and which parts to allow to decline a little longer. But a combination of the IoT and AMI can give utility managers clarity into their operations—and improve the bottom line.

Todd Stocker, director of product management with Aclara, says his company collects all the data generated by advanced meters and mines it for places to improve the utility’s infrastructure. In one case, Aclara performed a meter “right-sizing” project to address inefficiencies in a water utility’s 40,000-endpoint service area.

“We looked at the consumption data day in and day out and determined that utility was losing $1.4 million because the meters were improperly sized,” says Stocker.

In one part of the client’s coverage area, he says, Aclara found that the utility’s meters were too small. They simply couldn’t track the volume of water passing through them. The utility installed the meters with low-flow customers in mind, but later development brought customers who demanded more water than planned.

Bigger meters aren’t always the solution, Stocker adds. He also worked with utilities that installed large meters expecting water-guzzling customers, only to find that the high-flow meters didn’t notice the handful of gallons per day actually passing through them.

Aging meters can also pose a financial threat. “Meters never fail in the utility’s favor,” says Stocker.

But, he says, Aclara and other firms can run data diagnostics to spot the meters that have lost accuracy. “It’s really looking at the consumption over time,” explains Stocker. “Assuming significant changes don’t go on within the dwelling. . . the patterns are pretty consistent.”

The utilities’ diagnostics need only look for a long, slow trend in declining meter readings. Those, Stocker says, are usually the meters that need to be replaced.

He adds that utilities equipped to run this kind of diagnostic should run it frequently. If meters never fail in the utility’s favor, the meter replacements never work in the customer’s favor. When utilities wait too long between meter replacements, customers can see a big jump in their bill—which makes for poor customer service.

But if utilities vigilantly check for failing meters, Stocker says, they can spot the trend and install replacements before customers will notice a difference.

Brown at SUS notes that utilities can also recruit customers to help maintain infrastructure. Through SUS’s free Smart H2O app, California residents who spot a water waste issue such as a broken water main can alert utilities in seconds.

All the user has to do is use the app and their smartphone camera to document the failure. Then the app sends the picture of the broken pipe or water bubbling through the street to the appropriate water utility based on the user’s location.

IMPROVED OPERATIONS

As water utilities use the IoT to move their customer service team into the 21st century, they can use a different set of sensors and algorithms to improve the efficiency of their maintenance and repair crews as well. Steve Ehrlich with Space-Time Insight (STI) says his company has built a system that uses complex math and simple sensors to help workers complete repair jobs as efficiently as possible.

The sensors adhere to tools and help track their proximity to the worker, a truck, or another home base.

“Being able to do that allows us to track not only where those things are, but are they in the right place,” says Ehrlich.

If a worker leaves a construction site without one of the tools he entered with, for example, the system can alert the driver that he left the tool behind.

The same system works for water utilities. When a pump repair or replacement calls for a specialized tool, the maintenance manager can use the sensors to see where his crew left it after the last job. That knowledge can help avoid lost time scrounging for the tool the morning before a repair.

Other technology from STI can help automatically plan fluid workflows for maintenance and repairs with minimal human oversight. STI software actively monitors the functionality of all sensor-equipped nodes within a partnered utility’s service area. When a pump drifts out of its ideal operational band, STI’s software knows the node’s full history—its age, its capacity, its condition, and previous repairs performed.

Based on that, the program decides what priority to give the repair. Then, it plans each work day knowing the condition of every asset in the field, the location of every tool in the utility’s arsenal, the capabilities of every worker, and the difficulty and location of every job. This approach can cut down on urgent repairs and redirect the utility’s work toward improving efficiency and margins.

While these offerings represent an iterative improvement on existing supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and predictive analytics systems, STI separates itself by offering a program that can make on-the-spot decisions for workers in the field. When a worker goes out to perform a simple, routine repair on a pump and arrives to find that a tree has fallen across the site, STI has an answer.

The repair crew can pull up the program on a phone or tablet, enter a few details, and get a response in a few minutes. The system will account for the individual worker’s qualifications, their tools on hand, their job plan for the rest of the day, the tools, qualifications, and tools of nearby crews, and even the weather to choose the best course of action.

“We’re entering the era of the machines making the decisions for us,” says Ehrlich. “The reason we need that is because there’s too much information for the people to make the decisions.”

THE SOUND OF LOST MONEY

As Aclara pushes the state of sensing and metering technology, Stocker says its partners can now pinpoint and prioritize leaks in their pipes by using acoustic sensors. Through the company’s STAR ZoneScan program, utilities use magnets to attach acoustic loggers to the inside of valves at regular intervals throughout pipe networks.

Each night—when water use is at its lowest and system noise is at its quietest—the microphones capture the hiss of flowing water. By coordinating the sound from several loggers, the ZoneScan program can generalize the location. But the system also gives the utility a sense of the leak’surgency.

“If the sound profile is changing over time,” says Stocker, “it may be catastrophically failing.”

Aclara is also working on a pressure-sensing system that will give utilities better visibility into the pressure profile across their service territory—something that would be a big step forward for a lot of utilities.

Delivering water is an old industry, and one that’s often saddled with decisions made decades ago when utilities had limited access to granular data. Many early water systems, Stocker says, were built on a philosophy of “you put enough pressure in one end of the pipe, and as long as you get water out the other end, you’re okay.”

This approach leaves many utilities—particularly those with gravity-fed systems—with pressure imbalances that workers often relieve through wasteful means. Stocker points to the classic example of utilities opening fire hydrants to relieve local pressure spikes.

Utilities that get a better sense of water pressure across their system, he says, can adjust valves and inputs to ensure that all customers get adequate pressure and clean water while eliminating the need to crack fire hydrants.

Stocker says Aclara hasn’t yet made its fixed network pressure sensors available to utility clients (it’s in the proof of concept stage), but it aims to soon.

“[Possibly] within the scope of this year,” says Stocker. “In terms of utility timelines, it’s like tomorrow.”

WHAT ELSE COMES TOMORROW?

The far-off vision of the IoT for AMI sounds like something out of science fiction. One day soon, data from parking meters, stoplight cameras, and Internet-connected smart-home devices may all feed into databases controlled by public utilities. Algorithms will analyze that data in real time, and issue commands valves and pumps to optimize water pressure for that exact moment and its exact conditions.

That future requires buy-in from water utilities—which still feels like a tough sell to some people working in AMI.

But Tim Schwartz, with Master Meter, thinks that it’s only a matter of time before more utilities see the value in AMI, IoT, and everything that comes with it. “We are really moving into an IoT era,” he says. “Item after item is connected.”

Modeling Future Networks

Technology makes complex processes easier. A new software package from XP Solutions facilitates water distribution and transmission network modeling. It offers a clean interface for fast modeling development and integrates with both GIS and CAD systems to incorporate existing resources.

The open-source software expands the reach of traditional water models through reports and results tools. It also allows users to import EPANET, overlay results, and manipulate designs with WYSIWYG editors so that variations are visible.