Images of people in poverty or caught in a natural disaster show that lack of safe drinking water continues to be a major global health threat. We need to look no further than Haiti’s cholera outbreak after Hurricane Matthew struck in 2016 to see the misery. At the same time, reports from the United Nations indicate that the situation is improving as incomes and living standards rise in emerging nations. However, access to secure and safe water supplies for everyone depends on whether the threats or the solutions win in the long run.

Threats from natural causes such as floods, droughts, and earthquakes are certain to continue. Human causes such as civil strife and poor governance make things worse. Efforts to improve drinking water will continue through combined efforts of governments, businesses, individuals, and donors, but water management will be a challenge as nations struggle to shore up infrastructure systems while protecting the environment. The contexts are different—for example between the wealthy and poor countries—but the core issues are similar. People in poor villages need the same level of water safety as those in high-income countries.

The problem of safe drinking water has evolved along with economic and social development. When Dr. John Snow discovered the link between drinking water and cholera in 1854, the basic science of water treatment was not understood. Now, the science and technology of safe water are advanced, but stresses of population growth and urbanization create new challenges, especially to reach the world’s poor with safe and reliable water. In Dr. Snow’s day, physicians had a leading role in water safety, but the baton was passed to water professionals who developed effective systems that work well under the right conditions. Now, greater challenges are posed by social issues of growing villages and poorly governed cities in poverty-stricken regions, where the rule of law may be weak.

Given the local character of drinking water safety and the difficulty in assessing it, the number of people with safe and reliable water across the globe is not known precisely, but the struggle to fix the problem demands our best collective efforts. These require us to understand the extent of the problem insofar as it can be measured. This article explains the current situation and why monitoring and assessing the global status of safe drinking water is important but challenging. It also outlines ways in which water professionals can apply their expertise to help improve water systems around the world.

HOW MANY PEOPLE HAVE SAFE AND RELIABLE WATER?

Although global statistics of access to drinking water are available through United Nations agencies, water safety and reliability are difficult to quantify. They involve multiple factors that vary spatially, even between rich and poor neighborhoods and especially in low- to middle-income countries. Neither the indicators nor the monitoring systems are effective on a widespread basis and even in the US, where data is relatively abundant and accessible, they are difficult to synthesize and report. Regardless, general conclusions can be reached about water safety and reliability by combining socio-economic statistics with data on system performance, health, and governance.

Socioeconomic statistics are surrogates for levels of water services because the global condition of drinking water access and safety varies among haves and have-nots and mirrors the distribution of wealth. In high-income countries like the US, most people take safe, reliable, and affordable tap water for granted, but in low-income countries most people lack it. According

to statistics from the World Bank, in those countries, 10% of the world’s population lives on less than two dollars per day and many more can barely cover basic necessities. In between the extremes of rich and poor countries, billions of people have water services, but they lack around-the-clock reliability and are unsafe.

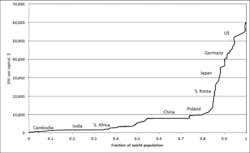

In 2015, world population was estimated at 7.35 billion and the World Bank classified countries as low-, middle- or high-income by gross national income (GNI) per capita. Figure 1 illustrates the sharp contrast between rich and poor in the world. Some 80% of the global population is still waiting to join the affluent group. It is evident that conditions such as in the US are the exception and most people live in much different economic conditions. Of course, these general statistics mask the fact that emerging elites, such as in China, are beginning to enjoy higher living standards.

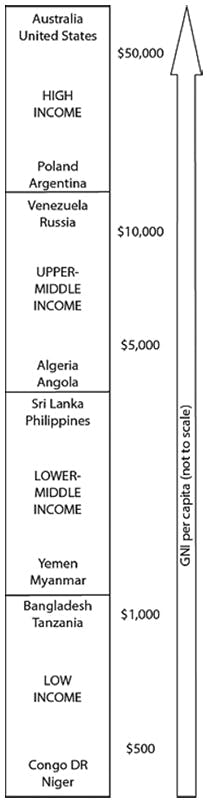

To form a valid picture of drinking water service levels, it is necessary to examine conditions in individual countries. To do that, the World Bank database of countries can be used. It contains information on 219 countries, but many are small, and some 61 of them are home to 90% of the global population. Of these, 14 are high-income; 16 are upper-middle income; 19 are lower-middle income; and 12 are low-income.

To illustrate variation by income among the countries, Figure 2 shows examples of the highest two and lowest two countries for each income group. The other countries are not shown to avoid unneeded detail. The income levels are not to scale so that a gradual difference from rich-to-poor countries is more evident.

Gross National incomes

Ideally, data on the percentage of time water is safe would be available and could be used to infer the reliability of water services. Such performance data may be available at treatment plants, but monitoring water condition in distribution systems is a more daunting challenge. Performance indicators for water systems are evolving but their status for global water supply is basic and only intended to provide an approximate picture of water access and safety. This approximate view is illustrated by the concept of the “water service ladder,” which was introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) to describe drinking water access across populations. It has three rungs for “unimproved” water sources, “improved” water sources, and “piped water on the premises.”

The income categories are used by UN agencies to track water supply levels as they relate to diseases and mortality. The main indicator is percent of people who have access to services at different levels. The data are reported by the Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP), which is sponsored by WHO and UNICEF, two agencies, which were created after World War II to address urgent problems of refugees and degraded conditions.

JMP’s programs apply mostly to low-income countries where most people do not get safe water from organized utilities. The data is based on household surveys and modelling to provide nationally representative results for international comparison. The JMP defines drinking water as water used for domestic purposes with the source less than one kilometer away and with a reliable capacity of at least 20 liters per capita, per day. An improved drinking water source is one that, “by the nature of its construction and when properly used, adequately protects the source from outside contamination, particularly fecal matter.” JMP’s most recent estimates are that about 663 million people still lack access to improved sources of drinking water. However, the definitions about access to water leave many loopholes where water can become unsafe, and the challenges of obtaining accurate data lead to many approximations. This has led to researchers developing different estimates of the global level of water safety, sometimes with large variations from the official JMP estimate. Therefore, with no consistent way to assess when water sources are properly used, this creates uncertainty as to water safety.

Because successful system operation requires effective regulatory systems, governance data can provide clues as to whether safe water is available. The World Bank reports indicators of governance, such as government effectiveness, rule of law, and absence of corruption. These can be shown to correlate to effectiveness in operation of water and sanitation programs. This is evident in a series of national case descriptions, which were sponsored by the World Bank. The case descriptions provide insight about the determinants of safe water: whether water supply is continuous or intermittent; whether an independent regulator is operational; whether there are frequent reports of waterborne sickness; and even whether there is an organized water supply industry.

WATER SAFETY BY INCOME GROUPS

By combining data on socioeconomic levels, services, health, and governance, a picture of the global safe water picture comes into focus. It shows that safe and reliable drinking water services vary even among the high-income countries. The safety of drinking water in the US is tracked at the local level, and utilities are required by law to issue annual consumer confidence reports. The situations in the European Union and Japan are similar. At the lower end of the high-income group, such as in Argentina, water safety is more problematic and the percentage of piped water on premises is lower than in the US, Japan, or the European Union. In all high-income countries, it is common that some problems persist in smaller systems.

The middle-income countries comprise a very diverse group. The upper subgroup spans from Venezuela and the Russian Federation at the high end, to Algeria and Angola at the low end, and includes Brazil and China. The lower subgroup spans from Sri Lanka and the Philippines, to Kenya and Myanmar, and includes Indonesia, Nigeria, India, and Pakistan. For these countries, national data on safe water is highly variable. The access to improved sources of water as reported by the JMP is high, but this statistic masks the jeopardy to water customers caused by poor services.

Poor services are indicated by the World Bank case descriptions, such as in Venezuela where intermittent water supply is often the case. The Russian Federation also struggles to provide safe and reliable water everywhere. At the lower end of the range, the levels of service are still lower, with many towns having intermittent service.

Because drinking water conditions vary so widely in middle-income countries, I contacted a small group of water industry academics, practitioners, and research managers representing seven of the countries to ask if the water is safe to drink 1) anywhere in the country, 2) safe only in a few zones of large cities, or 3) generally unsafe in many places. The group represented Brazil, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, South Africa, Peru, and Turkey and there was a high convergence of opinion that:

- Water is sometimes safe in big cities, particularly in wealthier zones, but people often do not trust it and commonly treat or boil household water;

- While treatment systems may be effective, distribution systems are in poor condition and water services may be intermittent;

- Sometimes water may be safe in specific zones or buildings, mainly due to point-of-entry treatment systems;

- The use of purchased water from unregulated vendors is common;

- Small communities have more difficulty than larger cities.

According to the JMP, the countries in the low-income group has the lowest percentages of access to improved sources of water. The World Bank cases indicate that where piped water services do exist, levels of service are low and water is mostly unsafe.

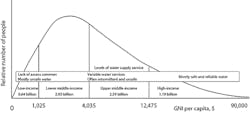

While the data does not enable an accurate assessment of the global extent of safe water services, it does point to a general conclusion. As shown in Figure 3, water supply services are mainly a function of income and water safety is a matter of haves and have-nots. The only group with safe and reliable water comprises the high-income countries, and even at the lower end of that group, water safety is problematic. The middle-income countries are very diverse, and in the lower part of the range few people have safe and reliable water services. Low-income countries often have high percentages of people who lack access to improved sources, and few people have safe and reliable piped water. There are always exceptions, of course. For example, in the high-income countries small numbers of users have unreliable and unsafe services and in the middle-income countries, some zones have safe and reliable services, particularly in higher-income parts of cities.

WHAT IS NEEDED?

Fixing the problem is not just about transferring expertise from high-income countries or increasing assistance from donors. After all, political and social problems do not give way easily to advice from foreign experts, and well-meaning projects may fail without sustained attention.

Water supply systems are developed locally, but in today’s interconnected world they may receive help from donors and other countries or international organizations. To mobilize this assistance requires us to understand the current extent and condition of water supply systems globally. However, global data is difficult to obtain and assess, particularly in some countries.

Currently, the global data of water supply access focuses mostly on low-income countries with the goal to assess health threats and poverty alleviation and not to assess the effectiveness of water services. The data program of the JMP faces challenges going forward: not only does the data contain many loopholes, it may not be considered relevant now that the original Millennial Development Goals of the UN have passed.

One possibility for improvement of global data is to incorporate performance data on services, such as percent of time water meets certain standards. However, there is currently no set of standards or data collection program for the global water supply community. Professionals in the health and water management sectors have shared interests in better data but it might be hard to convince a health agency such as WHO to take on an expanded role. Although the JMP is a small program and is dependent on funding from donors, it has built a foundation of monitoring and assessment methods and might be able to take on such an expanded role.

Water supply professionals can find multiple roles and opportunities to contribute toward improving safe water globally. The middle- and low-income countries have many experts, and they can join with other experts to comprise a global community of water supply professionals. International water associations can take leadership in global water supply and their members can act in the realms of education, training, technical assistance, and system development. By partnering with nascent national associations, networks of professionals with shared interests in improving the safety of water supply can emerge.

Many water professionals, from students through people at the end of long careers, want to be involved in the improvement of safe water services. It is important to them because they care about water and public health, and responsible outreach to different groups of people is built into canons of ethics across professional communities. Although these professionals are often attracted to their field by altruistic motives, their work on safe drinking water also affects economic development, travel, and trade. It even impacts global security because poor drinking water triggers disease and can drive increased migration and political tensions.

For some professionals, it can be more comfortable to focus on technical questions than on social issues and conflict. However, social and political issues must be confronted, even in high-income countries where systems must be permitted, financed, and maintained sustainably by people with diverse agendas. In low- and some middle-income countries, the non-technical problems can be confusing and seem to lack structure. Regardless of the situation, the starting point is to understand the problem holistically as a prerequisite to action.

No matter where opportunities occur, ways to act include paid occupations, volunteering, and donating to causes. Volunteer opportunities are extensive, such as participation in association committees, hosting visitors and students, guest lectures to student groups, and by influencing policy by writing, speaking, and direct advocacy.

As a university professor, I have seen many opportunities to participate in these activities and to discuss them with students and visitors. Three examples come to mind, with two of them being bookends on professional careers. In one situation, a student asks, “how can I become involved in international work.” In another that involves a late-career professional, the comment may be: “I’ve done business, and it’s been great, but now I want to give back.” In between these career bookends, another example is the professional who is involved along the way as a matter of community action such as in a service club.

In my own university, a number of students are involved with Engineers Without Borders or as volunteers with other non-governmental organizations (NGOs). One student started a successful small-scale water enterprise in Kenya as part of her master’s degree program in business. Mid-career professionals can go on mission trips, work with Rotary or other service clubs, and be involved with NGOs by volunteering or supporting them financially. End-of-career professionals can join NGOs as full-time staff or volunteers. There are many ways to be involved, and the global problem of water supply is another opportunity to apply the African proverb “it takes a village to raise a child.” The village is the global community of water supply professionals and the child represents the safe and reliable water systems they help to develop.