Springing from the Santa Cruz Mountains in central California, the San Lorenzo River rushes 29 miles through state parks, quaint mountain towns, and the heart of downtown Santa Cruz, where it becomes a channelized urban stream with a seasonal estuary.

As with many rivers in California and the American West, the San Lorenzo was an economic driver in the 1800s, providing water for the lime kilns and the logging industries that built San Francisco and the Central Coast. In the 1900s it was a hub for recreation and statewide tourism, drawing thousands of tourists to the thriving runs of steelhead and Coho salmon. Yet Santa Cruz’s proximity to its most beloved water body was mired in trouble. Homes and businesses constructed in the floodplain were destroyed by periodic flooding, which also claimed lives. The Christmas Flood of 1955 devastated downtown Santa Cruz and resulted in the construction of a levee system by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The levees channelized the river, altering its habitat and dynamism and creating a physical barrier disconnecting the Santa Cruz community from this once treasured natural resource.

Today, the San Lorenzo River is still the main drinking water source for 100,000 people. It provides habitat for endangered Coho salmon and threatened steelhead. Despite these important natural resources, the river doesn’t meet state water-quality standards, and its habitat is degraded. It is listed on California’s 303(d) list of impaired water bodies for pathogens, nutrients, and sediment.

For years, the city and county agencies had been working to address pollutants in the San Lorenzo River, yet water quality remained impaired. In 2013, the Coastal Watershed Council (CWC), a nonprofit with an aptitude for leading citizen science and community engagement, convened the San Lorenzo River Alliance, uniting government agencies, local businesses, nonprofits, and community groups around the common goal of reconnecting a healthier San Lorenzo River to a thriving community.

CWC realized that while many aspects of the river needed to improve, water quality, and specifically bacteria levels in the river, needed to be addressed. People wouldn’t be drawn to a river that was polluted or had the reputation of being unsafe to swim and play in. There was no better place to start than in the city of Santa Cruz, where much of the population in the watershed is concentrated.

To address water quality, the alliance formed the Water Quality Working Group with local agencies, nonprofits, and concerned citizens steeped in regional knowledge and a deep love of their watershed. The group included water-quality experts and stormwater engineers from the City of Santa Cruz Public Works and Water Departments, the County of Santa Cruz Environmental Health Services, the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board staff, and nonprofit organizations like the Surfrider Foundation and CWC. The group committed to improved sharing of water-quality data and devised a unified, holistic approach to improving water quality, combining science, public education, and policy.

In 2011, a total maximum daily load (TMDL) for pathogens was approved by the Central Coast Water Quality Control Board, outlining the parties contributing to elevated fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) in the river. The TMDL was based on data showing that the San Lorenzo River had a track record of exceeding maximum amounts for fecal indicator bacteria E. Coli, enterococcus, and total coliform.

Thus the objectives of the Working Group were twofold: provide a clean and healthy river as a resource for the community to play in and enjoy, and meet the pathogen TMDL requirements. The working group started out meeting monthly and held meetings only when a majority of the membership was able to attend. As group facilitator, CWC fostered an open dialogue among all working group members, recognizing and creating space for all participants to voice opinions, participate in decision-making, and shape strategy.

In 2014, CWC technical director Armand Ruby guided the working group in creating a framework for addressing the pathogen TMDL using an iterative process by 1) monitoring surface waters to characterize the impairment in the watershed, 2) identifying and prioritizing bacteria sources, 3) identifying best management practices (BMPs) to address those sources, and 4) implementing said BMPs. The strategy will be repeated, starting again with monitoring to evaluate the effectiveness of the previous steps, with outcomes informing next steps until the San Lorenzo River meets water-quality objectives.

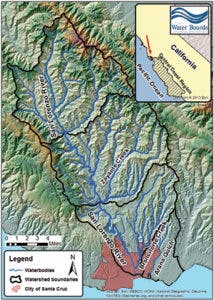

The strategy allows the working group to eliminate sources in the watershed in a targeted and economical manner. Recognizing the geographic range of the impairment in a 138-square-mile watershed, the working group members agreed to focus first on the lower San Lorenzo River, a high-density urban reach extending 3 miles from the city limits to the river mouth leading to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

watershed

In May 2014, the working group began the TMDL strategy with a six-month study of six sites on the San Lorenzo River and at the confluences of Branciforte and Carbonera Creeks. Many years of monitoring by city and county agencies had effectively quantified levels of ubiquitous FIB. However, a monitoring methodology to discern from where the FIB was coming, and more specifically if it was from human sources or non-human sources, had not yet been applied to the San Lorenzo River. To meet the TMDL requirements, working group members would need to show they had reduced FIB in the San Lorenzo River by addressing all controllable sources.

Accordingly, the working group developed a water-quality monitoring approach using multiple lines of evidence to determine sources of bacteria in the lower San Lorenzo River. By testing for constituents that mark human contamination, such as caffeine, human bacteria DNA, and certain human lipids, the working group would be able to determine if high bacteria levels were linked to human sources. This was key, as all harmful bacteria levels were targeted to be reduced, but the TMDL required that human sources of bacteria must be eliminated.

Field monitoring was led by the CWC staff and citizen science volunteers with the technical direction of working group partners. Monthly samples were collected and tested for FIB and human markers: fecal sterols and stanols, human bacteroides, and caffeine. Caffeine analysis was conducted by the City of Santa Cruz Wastewater Treatment Plant staff, while FIB and human bacteroides lab work was done by the Santa Cruz County Environmental Heath Lab staff. Fecal sterols and sterols were analyzed by Physis Laboratories in southern California.

The outcomes of the 2014 monitoring study clarified that human waste was only a small bacteria contributor. Caffeine, commonly used as an indicator of human sewage, was reported below the analytical detection level in all samples. Human bacteroides, an anaerobic bacteria found in the human gastrointestinal tract of humans, were detected at quantifiable levels in only three of the 36 samples collected. In the fecal sterols and stanols analysis that measures the presence of species-specific proteins, two of 36 samples indicated the presence of human waste, while 32 of 36 samples exhibited indications of avian, or bird, contributions.

The lower San Lorenzo River is a shallow, low-flow habitat for young fish, insects, and high grasses that supports 238 diverse bird species. Even if the group enacted more roosting mitigation or reduced trash around the river, avian bacteria would likely be uncontrollable. The working group considered the possibility that despite all attempts by the group to reduce controllable sources of bacteria, the lower San Lorenzo River may not be able to meet the TMDL because of inputs from resident and migrating birds.

With this in mind the group began to consider how controllable human waste and anthropogenic sources of waste were getting into the San Lorenzo River. In 2015, members of the working group created and analyzed a conceptual model showing how bacteria move directly into surface waters, or indirectly into the river through the municipal separate storm sewer system (MS4) via rainwater or urban runoff. Study outcomes from 2014 helped map these pathways and understand the geography of bacteria levels in the lower watershed.

This process produced an extensive list of likely bacteria sources coming directly from humans, from pets, or from domestic and wild animals in the watershed. To determine which sources to address first, the working group evaluated and scored each one on its risk to human health, magnitude of impact, frequency of deposition, how easily it is transported to the San Lorenzo River, and how controllable it is. Sources that scored higher were considered top-priority bacteria sources that the working group should focus their efforts on immediately. Priority sources to be targeted included faulty private sewer lateral connections and septic tank systems, homeless encampments, pet waste, and livestock manure.

In the spring of 2016, the working group began identifying which BMPs would most effectively address these priority sources. It convened a subgroup of stormwater engineers and public outreach staff with experience in BMP implementation and stormwater management. Members of the subgroup met monthly and reviewed BMPs implemented by city and county departments as well as BMPs implemented by nonprofit partners like Surfrider and CWC and other community groups. Finally, the subgroup created a comprehensive list of BMPs currently being implemented and a list of BMPs that the subgroup recommended for implementation.

To stay motivated through this thorough, diligent, and at times repetitive evaluation process, CWC staff facilitated opportunities for the subgroup members to share what motivates their water-quality work, beyond just checking a box on a permit requirement or “it’s my job,” and what impact they want to make on the San Lorenzo River watershed. Those moments of perspective successfully re-energized everyone, reminding participants that the human elements of personal motivation and team dynamics are just as necessary as stormwater expertise in a successful project, particularly with the lofty goal of addressing challenging problems that past efforts only partially solved. (See some of the members’ comments throughout the article).

Based on the prioritized BMP recommendations from the working group, the City of Santa Cruz Public Works staff developed a sewer lateral ordinance that requires the inspection and repair of sewer lateral of a home at point of sale. Many homes in Santa Cruz have clay sewer laterals or pipes that connect the household plumbing system to the city’s sewer mains. Over time, these pipes can crack or split, allowing bacteria-laden sewage to seep into the ground and eventually enter the river. The draft ordinance, to be implemented starting in fall 2017, will require the coordination of homeowners, City staff, realtors, and plumbers to address this bacteria source.

To complement this policy change proposed by the City, CWC set out to develop a public information campaign to support the new policy and teach the community about the environmental impact of leaking sewer laterals. With recommendations from the working group, CWC expanded the scope of the campaign with two more household sources that can be addressed through individual behavior change: pet waste and incidental flows, or human-caused dry-weather runoff that contributes to biofilm growth in the MS4 system.

The campaign utilizes radio PSAs, public meetings, digital collateral, and earned media to share information about sewer lateral leaks, pet waste, and incidental flows along with simple ways that each resident can make a difference. These initial education efforts and the sewer lateral ordinance focus on the lower San Lorenzo River in the city of Santa Cruz, with potential expansion into the upper San Lorenzo River watershed.

The Water Quality Working Group is optimistic that the focused TMDL strategy will be effective at reducing bacteria and supporting a healthier San Lorenzo River for the Santa Cruz community. Already the iterative approach has begun a new cycle of the four-step approach: the working group began its second phase of dry-weather bacterial monitoring of the river in May 2016. Monitoring was performed at the same sites as in the 2014 study, with the goal of developing data in a wetter, near-normal-precipitation year to compare with the 2014 monitoring performed under drought conditions.

The outcomes of the 2016 study are currently being analyzed and will be used to further refine the working group’s understanding of bacterial sources and pathways and the tools needed to address them. Funders of this work included the City and County of Santa Cruz, the Community Foundation of Santa Cruz County, the Rose Foundation for Communities and Environment, and the Helen and Will Webster Foundation, along with the donations of individual community members in the Santa Cruz area to CWC.

NOT JUST ANY STORMWATER MEETING

Any high-functioning collaboration is made possible by the solid working relationship between partners. The same is true for the Water Quality Working Group in Santa Cruz, CA, that works to reduce bacteria in the San Lorenzo River. To maintain and strengthen partner relations, staff from one partner organization, the Coastal Watershed Council, employs a simple but unique approach to meeting facilitation. Using facilitation and leadership techniques, staff create space in highly technical meetings for participants to reflect on and voice their passion and hopes for Santa Cruz and the San Lorenzo River. It’s this combination of the brain and the heart, science and passion, that drives this highly functioning team.

Meetings are opened with questions like “What motivates you to be here, besides a paycheck?” or “What are your hopes for the San Lorenzo River?” grounding subsequent conversations in what matters most to each participant. Partners learn what motivates each of their colleagues. Sharing builds unity around a common vision: in this case, a healthy San Lorenzo River embraced by the Santa Cruz community.

The group honors space for individuals to air out their concerns or challenges without getting stuck. If disagreement or frustration peaks in meetings, CWC guides the group back to the core values that each partner stands for.

Just how do you get a group of stormwater engineers to talk about personal feelings in the midst of conversations on MS4 systems and E. coli levels? While to some this might sound cheesy, it’s crucial to start from a common vision. The working group recognizes that, at its core, this work is not about water-quality requirements or stormwater infrastructure but about people and quality of life. It took thoughtfulness and finesse to add these emotional angles to the water-quality conversations. Yet tapping into the Water Quality Working Group’s collective energy transformed each two-hour meeting from a job requirement into a whole-hearted step toward long-term success.