Communication deficit plagues global water debate

Private sector water service providers must engage stakeholders and shareholders in the water debate in order to improve global water and sanitation coverage.

It was good to see Messers Zipparro, Sundaran and Scheel enter the lion’s den in the May 2005 issue of WWI (“Reversing the tide against public water utilities,” Vol. 20, Issue 3) by calling for municipal utilities to be seen on their own merits.

Unlike too many anti-privatisation campaigners, they have the courage to say that utilities must deliver what their clients want, rather than what their political backers desire. What we really need, however, will be when both sides of the public versus private sector service provision argument learn to engage with each other in a manner that serves the interests of improving access, service quality and sustainable resource management.

From my experiences over the past few years and the alignments of the various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), it is sadly evident that the Fourth World Water Forum in Mexico, to be held in March 2006, is set to go the way of Kyoto in 2003, where special interest anti-private sector participation (PSP) groups will concentrate upon hugging each other, rejoicing in the sound of their own voices while the water and sanitation Millennium Development Goals slip ever further out of reach.

The problem has been that the private sector has done so little to enjoin with stakeholders in the water debate, let alone try to educate shareholders about the broader issues involved at home and abroad. To my knowledge, neither a company nor industry association has published what could be regarded as a rigorous, peer-reviewed, data-driven and fully sourced attempt to address anti-privatisation arguments. Certainly, RWE Thames, Suez Ondeo and Veolia Water have led the way with some commendable efforts, but these are all in-house publications, reflecting internal experiences that can therefore be - even if quite unfairly - dismissed as corporate public relations.

In contrast, a plethora of academic and quasi-academic publications have attacked the notion of private management and funding. Lobbies sponsor much of this work with the sole aim of generating anti-PSP literature. Meanwhile, academic grant funding is usually going this way because the dearth of support for unbiased research on the PSP issue means that it is almost unrepresented in academia. This means that books such as Barlow & Clark’s Blue Gold (2002) have achieved almost iconic status within the anti-private sector lobby despite its evident inaccuracies and inconsistencies and a central message calling for domestic water to be provided free of charge, with its costs borne by industry.

Zipparro and his colleagues wonder why funding flows have seemingly dried up for municipal projects. I suspect that the reluctance of multilateral institutions to invest in such projects is more to do with the fact that when water is seen as being “free” and that cost recovery even for operations and maintenance services is regarded as acting against the popular interest, less funding will be available for new infrastructure and services. Thus responsible public service providers must raise the standard of universally affordable water services based upon full cost recovery. Commercialisation and open contract award processes need to be seen as a window of transparency that can drive out corrupt and inefficient practices to the benefit of the commons.

The private sector serves an estimated 560 million people through formal contracts, against some 375 million in 2000. This increase can be attributed to a shift in funding towards markets that are considered “safe,” such as China, instead of markets where a relatively small amount of funding and management expertise, correctly mobilized, can vastly improve services more cost-effectively in the short term.

A dearth of data and ideals

I have lost count of the meetings with private sector players where I have been presented with an executive summary of a well meaning programme for action, such as the Global Water Scoping Process, even though it is painfully obvious that anybody concerned about the issues had downloaded every technical annexe they could get their hands on months beforehand. The people who are managing the private sector’s public profiles are often wonderfully well intentioned, but have been left well behind by the whirlwind of anti-private sector initiatives.

The most exasperating episode I have encountered has been appeals for data about what the private sector can contribute from various non-financial (and therefore non-aligned) multilateral water and aid agencies about the role played in service extension to the poor by the private sector. Why is the private sector so shy when so much can be done and has been done? To give a few examples, I have written to these organisations about:

Yerevan, Armenia: An operations and maintenance contract for the Italian water company ACEA, supported by a World Bank loan, resulted in a 13 percent increase in customers with water bills accounting for eight percent of household revenues for the city’s poorest 25% of people in 2002 falling to four percent of household revenues by 2005. Water provision has meanwhile increased from 6 to 16 hours per day.

Casablanca, Morocco: Suez (France) was awarded a 30-year concession in 1997. By 2002, connections had increased by 34 percent and water losses had decreased by 28 percent. The introduction of block tariffs and low-income customer connection targets saw 65,000 low-income households gaining first time connections by 2004.

Manila, Philippines: Since 1998, the Manila Water concession has increased the number of households supplied with water from 325,000 to 581,000, while improving 24-hour coverage from 26 percent of the population to 93 percent. This includes 740,000 of the city’s poorest people, resulting in a 36 percent fall in infant mortality related to diarrhoea.

Tragedy of the commons?

The most bitterly ironic example is to be found when comparing the development of pro-poor water services in Bolivia. Water is a sideshow in the politics of private sector participation in Bolivia, which is chiefly driven by resentment over a legacy of discrimination against the country’s indigenous majority. Independent assessments about the events leading to the ending of the Cochabamba and La Paz / El Alto concessions point to a far more complex (and depressing) picture than is traditionally hailed by anti-PSP commentators. Indeed, the Cochabamba situation highlights the negative impact of special interest groups, such as the rich, privileged class in Bolivia, and the lack of progress made in the political vacuum created. Essentially, the Bolivian upper class are not supportive of private sector control of the water supply because it means the poor will win cheap access to “their” water.

In 1997, a 30-year water and sewerage concession for La Paz & El Alto, serving 1.34 million people was awarded to Aguas de Illimani (ASIA), a consortium led by Suez of France (55 percent), along with Bolivian and Argentinean investors. The contract was designed to pre-empt affordability concerns; labor provided by customers would reduce the cost of connecting poor areas. Commun-ity involvement in infrastructure development was paramount, based upon gaining broad support from the outset. Projects only took place where at least 60 percent of the community supported them. Families not connected to the network pay an average of $4.78 per month for water through vendors, against an average of $1.55 per month for connected families. During 2004, ASIA increased drinking water services to 373,000 people and sanitation services to 435,000 residents (Table 1).

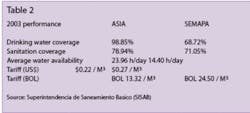

Service delivery and affordability under the concession can be judged by contrasting ASIA’s performance in 2003 with that of SEMAPA, the utility serving Cochabamba, the city which cancelled a water concession in 2000 (Table 2). So the “people’s victory” in Cochabamba is proving to be a hollow one. The local political climate has subsequently stymied investment in the region.

Forget corporate hospitality, let’s have some corporate action

My message to private sector providers is a simple one. If they believe they have a story to tell, please do tell others about it!

Perhaps the Gurria Task Force, which will unveil its deliberations at the Mexico City World Water Forum this March, has the best hopes of cutting through the cynicism and indifference that clouds the sector. The World Water Council's Task Force on Financing Water for All, headed by Jose Angel Gurria, the former Mexican finance minister and director general designate of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), needs to capture the imagination of the developed countries through proposals based on realizable objectives, such as mobilizing private finance for affordable sub-sovereign debt in developing economies.

Unfortunately, protestors broke up the Camdessus Panel presentation during the World Water Forum in Kyoto, Japan, in March 2003 within minutes, with a well-primed media at the ready. Three months later, debates over Iraq swept aside the session scheduled to discuss the Camdessus report at the G8 Evian Summit. If the Gurria Task Force can for the first time mobilise innovative research in a manner that cuts across old perceptions, the lives of thousands, if not millions of people across the world, could be improved.

Author’s Note

Dr. David Lloyd Owen is the managing director of Envisager, a UK-based water and waste management consulting firm ([email protected]). He has published several hundred articles on water financing and services and a number of books on the sector including the Pinsent Masons Water Yearbook (Seventh edition, 2005).

PSP challenges explored

In the past three years, various public and private organizations have unveiled ambitious PSP initiatives. For example, the World Business Council on Sustainable Development aims to define the business sector’s contribution to the PSP debate. PSP Water, run by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs and Swiss Re seeks new PSP approaches at the policy, operational and practitioner level.

The Global Water Scoping Process, jointly developed by the Brazilian Association of Municipal Water and Sanitation Public Operators, Consumers International, Environmental Monitoring Group, Public Services International, RWE Thames Water, BPD and WaterAid, aims to develop a multi-stakeholder review of PSP in water and sanitation.

The World Economic Forum’s Water Initiative seeks to apply best practice business techniques for water and sanitation and joint projects between the private sector and other stakeholders that highlight good corporate practice in water management and promote market-based instruments for water and watershed management. Their challenge will be to move the debate forward and bring their perspectives before a broader public.