Modeling Eases Major Sewer Network Upgrade

To address the challenges of improving water quality, the Louisville and Jefferson County Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD) in Kentucky has embarked on a comprehensive sewer improvement program that will greatly mitigate sewage overflows throughout Louisville Metro during wet weather.

Louisville, which is Kentucky’s largest city and bound by the Ohio River, is sited on the Kentucky-Indiana border. The new initiative is called “Project WIN” (Waterway Improvements Now). Planned upgrades under Project WIN will allow the area to comply with Clean Water Act regulations.

Justin Gray, an MSD Senior Technical Services Engineer, said that the work is being carried out to comply with a U.S. EPA consent decree, as is the case for many large cities in the United States. “The aim is to eliminate large sanitary sewer overflows and combined sewer overflows. We might do on-site treatment, plant expansions, diversion of pipes in areas of overflow, storage basins, and add more green infrastructure such as barrels, green roofs and pervious pavements.”

The city faces a major challenge: Louisville, with a population of over 700,000, has over 3,200 miles of sewer pipe, some 500 miles of which are over 100 years old. Currently, there are 111 active CSO locations that will overflow on average 30 times per year. In addition, during years with above-average rainfall, over 100 more locations in the separate sanitary sewer system might overflow.

MSD, founded in 1946, operates and maintains six regional wastewater treatment facilities, 22 small wastewater treatment plants, and 304 pumping stations as well as the sewer network, stormwater system, and the Ohio River flood protection system.

Many older U.S. cities, like Louisville, built combined sewers to carry both wastewater and stormwater, designing the system to overflow during periods of heavy rainfall. In areas of Louisville Metro with separate sanitary sewers, sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs) occur because of aging pipes that allow stormwater to infiltrate through pipe defects when the ground is saturated or due to illicit connections of sump pumps, roof drains and foundation drains to the sanitary sewer system.

When exploring solutions to these issues, the MSD has to be able to plan accurately for rainfall management. Thus, modeling is an integral part of both the control plan for the combined sewers and the separate sewer plan for the sanitary network.

The aim of the work is to eliminate over 200 overflow points within the next 20 years, at an approximate cost of $800 million. Gray explained that he became involved after the Consent Decree was signed and the program was in the planning stages. “The first big task, from my perspective, was to build sewer models for every service area — there are 22 in all, six for the main regional treatment facilities and the rest for the small plants.”

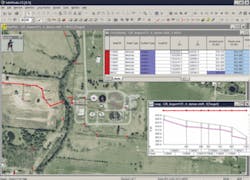

The existing models, in XP-SWMM format, were in various levels of detail and accuracies, as the MSD had never published a sewer modeling standard, and the modeling data was in the hands of various consultants. ”I got all the data and reviewed different software programs,” added Gray. He also undertook a great deal of investigation in reviewing software capabilities, including examination of detailed studies for other cities such as Atlanta and Sacramento, before deciding on InfoWorks CS.

The MSD also wrote a modeling guideline document to standardize future model development, and contracted six engineering firms to model the MSD system, buying and renting a number of InfoWorks CS licences. The modeling is hosted on MSD’s own Citrix server. Engineering firms log into the organization’s intranet to access the work, revise models, and run simulations. Up to nine modelers can access the system at one time, and all of the modeling and data files are hosted on this server.

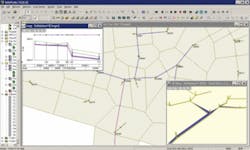

Having the data at one centralized point is useful, Gray noted, as it has been possible to continuously check on progress and share data. Engineers have also been readily able to explain issues. All of the models are now built, including an extremely large combined sewer model that is ready to be linked to three models of the sanitary system to create a massive model with some 45,000 to 50,000 nodes.

“It’s the first time we have had software with the ability to model the network as one entity and keep usability practical,” said Gray.

The MSD will be able to look at over 600 capital projects and is planning for a run incorporating all of the selected solutions to see how they work together.

“We are using the models to develop all of the initial solutions for the sewer overflows, including solutions such as storage, treatment, and diversion. We are going through the process of developing these solutions now,” explained Gray. Final sizings for pipes are being calculated along with storage alternatives such as in situ holding basins (space permitting), or transportation to regional storage systems.

The models will also be used to understand the extent to which the proposed green infrastructure will help ameliorate flows into the system.

“We will be using models of the green infrastructure to analyze how much impervious area can be disconnected from the overflow system,” Gray said.

It will involve gauging the public’s willingness to adopt systems such as green roofs and rainwater barrels, and the extent to which these are likely to function properly, to be able to predict with confidence the percentage reduction in demand on the system this is likely to create.

Plans will be submitted by the end of the year.

“It has been a pretty good experience so far,” Gray said. “We’ve run into some software and hardware problems, but we’ve been able to resolve the issues.”

The long-term control plan is due to take place over a 17-year period, and the sanitary sewer discharge plan over a 22-year term.

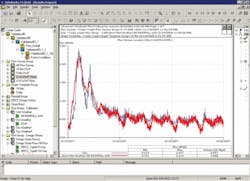

According to Gray, the models for the entire network were calibrated within nine months. “We didn’t think we could do it, but now we’re coming up with solutions, all done centrally. It has worked pretty well.”

Indeed, a long-term simulation for a 12,000 node combined sewer model over MSD’s server took just 18 hours compared with four days for a simplified 2,000 node model of the same system using a previous software package.

“It has certainly saved us a lot of headaches,” Gray said. “It has also saved money on consulting fees because the models run faster. The models have become a lot more useful.”

The models will be utilized again, once the detailed engineering design stage is reached, to support the work being done. They are being used for the MSD’s capacity assurance plan, which identifies systems, pipes and pumps that do not have sufficient capacity during wet weather. In addition, as requests come in from developers, simulations can be run to identify whether system upgrades will be needed to absorb the additional predicted flows.

One unexpected benefit relates to the MSD’s existing and mature GIS system.

“This system has a lot of layers of information,” Gray said. “We imported the GIS information related to sewers into InfoWorks, and took as much information from the old models as we could. Then we had to work through the missing data such as some invert heights, slopes, and pump station information using InfoWorks data flags to track the source of the information we were inputting.”

MSD can now transfer data back to the GIS and its asset management system, improving overall data quality.

Editor’s Note:

For more information on InfoWorks CS or Wallingford Software, contact [email protected] or visit www.wallingfordsoftware.com. uwm