Case Study: Yelm, Wash., 100 percent reuse program solves nitrate problem

By SYLVIE DALE

Associate Online Editor

YELM, Wash., Nov. 1, 2000High levels of nitrates seeping from septic tank leachfields had a Pacific Northwest city scrambling for a way to protect its drinking water.

But new legislation cleared the way for the town of Yelm to become the first in the state to propose reusing 100 percent of its wastewater. While doing so, the wetlands and park area have become pleasant attractions for visitors and have even hosted weddings.

For the past 20 years or so, communities around the nation have been reusing their wastewater, especially in water-scarce areas like California, Arizona, Texas and Florida. But the water was used primarily for irrigation purposes, like golf courses and parks. The thing that sets this community of 3,000 apart was its willingness to find new and diverse uses for the reclaimed water, according to Tom Skillings, President of Skillings-Connolly, Inc., and a project manager the reuse project in Yelm.

Situated just 65 miles south of Seattle, in the shadow of Mount Rainier, glaciers from the last ice age and the river have left the prairie soils very porous; the groundwater table is quite shallow. Yelm draws its drinking water from this shallow aquifer.

In the mid-l980s, routine testing revealed that nitrate levels were rising in the drinking water. Studies indicated the nitrates were coming from high densities of septic tank leach fields; the soil structure simply could not keep up with the densities, and the groundwater was adversely affected. About 61% of residents at that time were using individual onsite sewage disposal systems, according to records from the Thurston County Health Department. The levels continued to rise until the health department declared an emergency and directed the city to correct the problem.

As an immediate fix to stop the contamination, the city in 1992, began constructing a new Septic Tank Effluent Pump (STEP) system and aerated lagoon treatment facility, with provisions for a discharge into the Centralia Power Canal (a diversion of the Nisqually River used to generate electricity) and an emergency discharge directly into the Nisqually River.

The work was completed in 1994 with the understanding that the discharge permit into the environmentally sensitive Nisqually river would be temporary. The city had three years to find a way to stop the emergency discharge into the river, and five years to stop it from entering the power canal.

Initially, the city considered obtaining a land-application discharge; however, public acceptance and environmental standards at that time rendered this a non-option.

Then, as the new STEP system and treatment plant were being constructed, an opportunity arose. The Washington State Legislature passed the Reclaimed Water Act, 90.46 RCW. This new act encouraged the beneficial use of reclaimed wastewater and authorized and directed the Washington State Departments of Health and Ecology to establish the reclaimed water standards needed to develop such beneficial uses. Also, it directed the departments to initiate a pilot-project program that would provide technical assistance to communities that wanted to pioneer wastewater reclamation in the state.

The new Water Reclamation and Reuse Interim Standards provided the gateway for Yelm to solve its dilemma of how to stop discharging wastewater into the Nisqually River.

100 percent reuse

The City of Yelm applied for and received pilot-project status in 1994, becoming the first community in the State of Washington to propose reusing 100 percent of their wastewater.

But the issue of Water Reclamation in Western Washington, in rainy climates, is unique, Skillings said. The community didn't need the water throughout the year.

Western Washington's wet winters and short irrigation seasons forced Yelm to design beneficial-use options that were reliable year round.

The Interim Standards as written had not taken into account the need for year-round reliability, so the City of Yelm, its consultant Skillings-Connolly and the Departments of Health and Ecology worked together to come up with a list of acceptable uses for the water when it was not needed for irrigation.

Some of those alternative beneficial uses included recharging the aquifer, augmenting stream flows or creating and enhancing wetland habitat.

The state legislature amended the Reclaimed Water Act to recognize these new "non-consumptive beneficial uses," and stated that reclaimed water would no longer be considered "wastewater."

To seek the support of the community, the city and Skillings-Connolly engaged the public in discussions. The consultant gave examples of typical uses that were approved by the Interim Standards, and provided case studies where such uses were being implemented and accepted in other parts of the country. For instance, Irvine Ranch in California treats and reuses its wastewater to use it in many of the same ways that were being suggested to Yelm. The public not only became receptive to the idea, they began to see the value of the water itself.

Skillings-Connolly's primary strategy in its public involvement process was to let the residents give feedback on what uses they thought would be acceptable. Some said they'd believe the water was environmentally friendly if fish could live in it, so the engineers designed a catch-and-release fish pond stocked with rainbow trout.

The design placed the pond in a wetlands area that was attractive to look at and also finished the treatment process before the water was released.

The concept of Cochrane Memorial Park evolved as an outcome of a Health and Ecology requirement that additional polishing of reclaimed water be provided prior to infiltration into the shallow aquifer.

The consultant team proposed using eight acres of city land to create a wetland park that would include water features, constructed wetlands and the fish pond.

The citizens of Yelm endorsed the effort, and the project moved forward in 1995. Funding for the roughly $11 million project came from a number of sources, including a special appropriation from the Legislature, grants and loans from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rural Development, loans from the Department of Ecology, and monies collected through a Local Improvement District formed by the citizens of Yelm.

The reuse system, completed in 1999, consists of three elements:

1) a state-of-the-art treatment facility that produces up to 1 mgd of Class A reclaimed water

2) a "purple pipe" distribution system that delivers the reclaimed water to the beneficial use sites, and

3) the beneficial use sites themselves, which are located throughout the town.

The treatment facility is a simple Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR) process which also includes sand filters, serpentine chlorine contact tanks and a 6-million gallon lagoon.

Current uses include irrigation at the treatment facility itself, at Yelm Middle School, at two churches and at a residential vegetable garden. The reclaimed water is also used for school bus washing and hydrants are provided for fire protection. Future commercial applications of reclaimed water might involve car washes and concrete production. Additional rapid infiltration basins will be provided to enable the city to expand the capacity of the reclamation system to reuse 100-percent of the flow from the treatment facility.

Its centerpiece, Cochrane Memorial Park, is an eight-acre constructed wetland park with aquifer recharge. The water feature reduces the chlorine, and a freewater surface wetland further reduces chlorine levels and adds nutrients back into the water. The water then flows into a catch-and-release fishpond. Subsurface and surface flow wetland treatment ponds follow the fishpond to provide additional polishing and nutrient removal prior to aquifer recharge using specially designed rapid infiltration basins.

The new facility has only three operators, but only one is needed to keep the plant running. At night, the plant runs itself. If there is a problem, the alarm system calls or pages the operator on call at home. The web-based control settings can be accessed from anywhere with the right password.

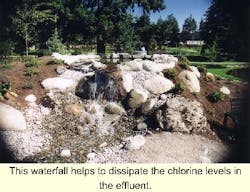

The plant has been running for about a year with 100 percent reuse, Skillings said. The effluent, at .3-.5 NTU, exceeds the state reclaimed water standard of 2 NTU, and even exceeds state drinking water standards of 1 NTU. The finished product is very low in nutrients, has no fecal coliform, and has a chlorine residual of .5 mg/l of chlorine at the end of the distribution line. This residual is dissipated by the wetlands at the mouth of the distribution line, after the water spends three days going a series of retention cells with aeration features (like waterfalls).

The algae buildup is very extensive in the process before the fish pond, Skillings said, but this is a normal process for natural or constructed wetlands. An aerator in the fish pond helps keep the dissolved oxygen levels at 7 or 8 ml/liter.

In the future, Yelm will build more wetlands and another fishpond at the Yelm High School, where students will have the opportunity to study the effects of reclaimed water upon the environment. This facility also will provide for aquifer recharge.

A reuse plan helped Yelm reduce its nitrate levels in the groundwater supply, according to reports from the Thurston County Health Department. It also cut down on water use for irrigation and did so in an attractive way that had a positive impact on wildlife. To date, the project managers have received no negative public comments at all.

Other communities are now, or are planning to emulate the process Yelm innovated. Olympia, Wash., the state capital with 50,000 residents, is using satellite facilities like that of Yelm's built into its community design. In addition to the benefits which Yelm derived from the project, such a project can also be used to reduce or completely bypass Total Maximum Daily Load limitations or augment potable water supplies in water-scarce areas, Skillings said.

"It's clear that it's the right thing to do and a viable, publicly acceptable way to deal with our water shortages and cleaning up the environment."