The University of Arizona may have stopped a potential coronavirus outbreak earlier this year by testing dormitory wastewater for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Just days after students returned for the start of the fall semester, sewage testing showed the presence of the virus’ RNA in raw wastewater samples from a particular dorm. The university tested all residents of the dorm and found two people who were asymptomatic but positive for the virus. Those students — who had tested negative prior to move-in — were then quarantined to stop others from becoming infected.

“We identified the [presence of] coronavirus in the sewer line coming out of one of the dormitories, and we estimated by the flow from that sewer line that there were somewhere between two and five people infected out of about 327,” Charles Gerba, professor of environmental microbiology with the University of Arizona, said.

“Sure enough, when the university infection control panel went and tested everybody for the virus, they found two people that were infected. They were removed from the dormitory, and when we tested the wastewater again the next day, it was negative.”

Since the initial test, Gerba says the University has continued to monitor wastewater on campus this way, then testing and removing infected individuals from on campus housing until they are well again.

“Because we have a confined population, you can determine [infection cases] by taking one sample once a day, and then if anybody is infected, [we can remove] them from the dorm so it doesn’t spread,” he said.

Research, including a study released in September by Yale University and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station say widespread wastewater testing can act as an early warning system for communities, and could provide better estimates for how widespread the coronavirus is because the practice would include samples from people who have not been tested and have only mild or no symptoms.

“Depending on the level of virus in the sewage, wastewater testing can also be a leading indicator of a worsening outbreak,” according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And, though it is not intended to replace clinical testing, it can help communities where COVID-19 tests are underutilized or unavailable.

At the University of Arizona’s Water and Energy Sustainable Technology (WEST) Center, Gerba said wastewater testing has been used for two purposes.

“One, to ensure [the virus is being effectively] removed by our wastewater treatment plants, but also to monitor the wastewater here and looking at the impact of interventions,” he said. “For instance, when the pandemic first started, we saw the rapid rise [of infections] in Tucson in the sewage. When stay at home orders went into effect, levels [of the virus in sewage] went way down.”

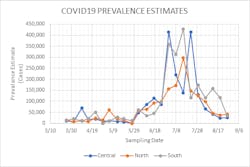

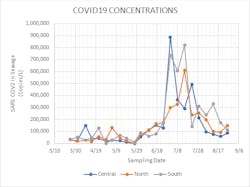

Around the Fourth of July, when the stay at home orders had been lifted for some time, Tucson’s sewage told researchers another surge of infections was imminent. Likewise, the levels of the virus’ RNA in sewage have gone down as mask mandates have gone into effect, providing “a clear indication of how well interventions are working, as well as future warning signs in our community,” Gerba said.

While wastewater testing could be a sensitive tool to monitor the circulation of the virus in a population, the method remains imprecise. It can spot infection trends, but it can’t yet consistently pinpoint the number of people with the virus or the infected individual’s stage of infection. That means it’s not yet quite as useful on a larger scale in cities, which don’t always have a university’s scientific resources or the ability to require people to get tested.

“In general, when it’s been presumed that a lot of people are infected in the county, you really do see a reflection of that in the [wastewater testing] data,” Kevin Lynskey, director of the Miami-Dade Water and Sewer Department, said. “In periods when there’s presumed to be a low infection rate based on [clinical] testing, it’s pretty consistent there, too.”

Lynskey said the data between large spikes (up or down) in infection rates is still valuable information to have.

“What I think our utility has been finding, along with all the other utilities [conducting this research] is that the information that comes out of the sampling programs is valuable directionally,” he said. “We know that there’s some work to be done, but if you average [our] three plants into one picture, the data has been fairly consistent with what we found in that community.”

A nationwide standard of wastewater-testing could alleviate some of the inconsistencies in results, but developing the protocol, especially considering other limitations around medical testing for the novel virus, will take time.

Today, the two most prominent testing methods are qPCR and digital droplet testing, but even within those two camps, there are multiple variations on how these testing methods are employed. For example, some laboratories are testing wastewater solids, while others test liquid samples taken at different stages in the treatment process. Some facilities require the samples to be pasteurized prior to testing, while others test raw wastewater. All of this can impact the strength of the virus’s RNA signal.

In a recent international summit on COVID-19, the Water Research Foundation (WRF) convened experts from around the globe to conduct a laboratory methods assessment to understand the factors that affect detection of the virus in wastewater samples.

“There is real potential behind sewershed surveillance,” John Albert, WRF’s chief research officer, said following the summit.

With several research projects underway, WRF is working with the CDC and U.S. EPA to develop minimum data requirements for COVID-19 detection in wastewater.

“In this short amount of time, the amount of resources that we were able to get together across the country and ask these critical research questions of, and the amount of research groups working on this is simply amazing. And to advance the analysis and really, the testing, so quickly, really shows that this concept of sewershed surveillance is here to stay.”

Albert said the next step is to establish a closer working relationship between public health agencies and wastewater utilities on the implementation of best practices for sample collection, analysis, and interpretation, and speedy and appropriate translation and communication of results to public health decision-makers.

With the coronavirus threat still looming, he said, sewage surveillance could become a “helpful addition in the public health toolkit.” WW

About the Author: Alanna Maya is editor of WaterWorld magazine. She can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Alanna Maya

Chief Editor

Alanna Maya is a San Diego State University graduate with more than 15 years of experience writing and editing for national publications. She was Chief Editor for WaterWorld magazine, overseeing editorial, web and video content for the flagship publication of Endeavor's Water Group. In addition, she was responsible for Stormwater magazine and the StormCon conference.