Implementing an Asset Maintenance Management Strategy… Where Do You Start?

By Tony Rojas and Jim H. Davis, CMRP

Asset maintenance management has been in the global water arena for a long time but has constantly undergone name changes as well as changes to its overall definition. Simply put, asset maintenance management can be defined as a continuous process improvement strategy for improving the availability, safety, reliability and longevity of physical assets (i.e., systems, facilities, equipment and processes).

The more well-known Asset Management Strategy (AMS) obviously encompasses far more elements than just maintenance. There are lessons to learn, though, in what the Macon Water Authority (MWA), in Macon, Georgia, USA, did to launch a sound Asset Maintenance Management Strategy (AMMS) for our various physical “equipment, process and facility” assets.

First, we’ll focus on major components of our AMMS and what each component requires. Next, we’ll look at details we put in place for the “care and maintenance” of our physical assets. Processes (as discussed herein) are nothing more than a collection or assembly of dedicated pieces of equipment, located in some building or area of the grounds, typically monitored and/or operated by some computerized logic system, human intervention, or both. Systems can be defined as water distribution, sewer conveyance systems and other essential appetencies.

AMMS Components

To start, a sound AMMS has to be viewed as belonging to and involving the entire organization, not just the maintenance department. The primary purpose of an AMMS and its accompanying components (programs, tasks, or activities, etc.) is to:

- Know exactly what assets you have (i.e., those you’re responsible for operating, monitoring and/or maintaining)

- Know precisely where your assets are located

- Know what condition your assets are in at any given time

- Understand your assets design criteria and how they’re to be properly operated and under what conditions

- Develop an asset care (i.e., maintenance) program that assures each asset performs reliably when needed

- Acknowledge and perform all of the above activities to optimize costs of operating your assets and extend their useful life at least to, if not beyond, initial design and installation goals.

Know your assets

It may sound simple, but identifying what assets MWA had wasn’t as simple as one might think, especially when considering the large amount of infrastructure it maintains and operates. The authority has infrastructure consisting of two wastewater treatment plants, one water treatment plant, 54 lift stations, six pump stations, 17 storage tanks and some 2,600 miles of sewers and water mains, i.e., pipeline.

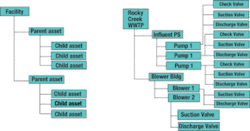

An asset registry spreadsheet was developed to be completed at each facility by the operations staff following the site treatment process train. Figure 1 shows the definition of the parent-child hierarchical approach used for the inventory collection.

Development of such detailed inventory data wasn’t possible for buried assets. While about 75% of the sewer conveyance system was inventoried and available on MWA’s geographical information system (GIS), details on the water distribution system existed on paper maps, in the minds of key staff members, or wasn’t available at all.

Know where they’re at

Again, this may sound simple, but how many times did we have to dig out drawing after drawing, snoop around physically, or try to track down the last person(s) who worked on a given asset to actually locate it? Worse case, with regards to in-the-field assets, what used to be easily locatable may now be hidden under a street or sidewalk.

A lot of the conditional elements we mentioned with regards to “knowing what assets we had” apply here as well. Still, with today’s GIS and GPS technology, this is becoming less and less of a problem, especially with more recently installed assets.

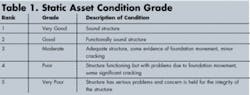

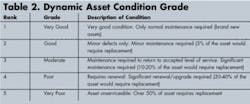

Know their condition

Knowing the condition of each of our assets has always presented its own set of problems… especially when those assets are “hidden” from normal sight (i.e., vaulted, underground or remotely located).

This situation dictated we have a procedure in place that requires us to do whatever inspections, preventive maintenance (PM) and/or predictive tasks (e.g., CCTV, ultrasonic scans, etc.) whenever we had the opportunity to do so and that we completely and accurately capture, document and store all related and pertinent information for easy access and review at any future point.

This information typically has to come from operators, maintenance crews, contractors and engineers… whoever touches that asset for any reason. That’s why we stressed earlier that a good AMMS wasn’t just a maintenance department initiative. It had to involve our entire organization.

Design criteria & proper operation

This element certainly isn’t germane just to utilities. Industrial manufacturing firms worldwide have to deal with this situation as well. Increased customer demands, diversity and modifications to equipment may cause us to push those assets far beyond their design capacity. If we do that for long, we’re possibly setting ourselves up for some major catastrophes. To monitor this situation, we would need to know what the design “specs” were, document them, insure the equipment is operating within those parameters, and maintain that equipment accordingly.

Asset care programs

Once we knew what assets we had, where they are, and how to properly utilize or operate them, we had to integrate a basic asset care program (call it maintenance if you must) to ensure those assets are ready to use (i.e., availability) and once engaged (turned on) will operate at or near the designed specification parameters until we disengage (turn off) that asset. This is known as reliability.

To do this, we had to have a clear picture of how we expected to run our maintenance program. We wanted to operate in a more proactive maintenance environment vs. a reactive one. It’s a proven that operating in a reactive mode costs two to three times more in costs labor, parts & materials, and loss of service than does operating in a proactive environment. Proactive means that (through Integrated Water Resource Management use of regular inspections, effective PMs, various predictive technologies, etc.), we’re finding problems before they occur, and “fix” them prior to actual failure.

Our proactive asset care environment now includes all of the techniques mentioned above, along with effective “planning and scheduling” and “work order feedback loops” to provide asset history. This will eventually allow our maintenance planners to do datamining, statistical process control (SPC), failure modes and effects analysis (FMEAs) and even better root cause failure analyses (RCFAs) when we do experience one of those unexpected failures.

Effective optimization

Acknowledge and perform all of the above activities to optimize the costs of operating our assets, and to extend their useful life at least to, if not beyond, what’s called for in the initial design and installation. This is where the “strategy” part came in which primarily fell under the responsibility of supervision and management. There were two basic requirements here:

1. To establish the proper “key performance indicators” (KPIs) for our asset care processes so that we could monitor (as often and as easily as we do our various operational activities, i.e., throughput) and determine such things as:

- Jobs in Planning Backlog

- Jobs Scheduled Emergency & Break-in Jobs Completed

- % Emergency & Break-In Jobs

- Scheduled Jobs Completed Schedule Compliance

2. To collect the rights kinds of data, at the right time, in a consistent format that allowed us to make “data-based” vs. best guess decisions. To know where and how we were spending our asset care (maintenance) money, we would have to have enough information in enough detail to know whether to “repair, refurbish, or replace” any given asset and what were the consequences of that choice.

Each of the components we needed to address weren’t always as simple to enact as one might have hoped, especially since our organization had been somewhat lax in incorporating many of these elements for many years. We realized that to do this, we had to retain the services of a professional AMMS consulting company to assist us with putting some of these things in place and “ramping us up” as quickly as possible before we could realize any true benefits.

Sound Maintenance

These are the six basic components of a sound “maintenance” asset management strategy:

- Work Identification & Control

- Job Planning

- Work Order Scheduling

- Preventive/Predictive Optimization

- Materials Coordination

- Scheduled Outage/Shutdown Coordination

Making it work in Macon

The Macon Water Authority controls nearly $280 million in assets and administers a yearly operating budget of over $41 million. It has about 210 employees that serve the water and sewer needs of 54,000 customers in the mid-Georgia region. The utility now has one of the most aggressive capital improvement and renewal/replacement plans in the state, with nearly $22 million in water and sewer projects in process. These involve line extensions and rehabilitation of aging infrastructure, including elevated water tanks, water mains, intake structures, lift stations, variable frequency drive (VFD) pumps, and sanitary sewer mains.

Work identification & control This is the most important component of the six listed above. Without this basic function in place, optimization of any of the others is virtually impossible. Absolutely no work should be performed on any asset (by our people or a contractor) without a properly generated and approved work order.

The only way we would be able to determine the true cost of operating and maintaining any given asset was to record each incident whereby “labor and material resources” are applied to that asset. The best way to capture this information was through a work order system that identified a specific piece of equipment, who worked on it, for how long, did what, and used what parts/materials to complete the job.

Equipment (i.e., work order) history files, collected through our newly installed computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) system, will become our primary source for accurate and relevant information with regards to the condition and cost of maintaining each of our assets and will tell us whether to repair, refurbish or replace that asset.

Job planning To do good job planning (i.e., pre-planned work), we had to have maintenance planners in place and well-trained on how to produce top-notch work order job packages. We found that an effective job planning process provided the following benefits:

- Quicker repairs on pre-scheduled work, projects and other tasks

- Better quality repairs and other work

- More efficient “wrench time” from technicians and maintainers

- Improved parts and materials costs and usage

- Improved safety on-the-job

- Less downtime, more uptime of systems and equipment

Job planning involves more than just identifying parts, it also involves:

- Scoping & estimating requirements for the job

- Determining actual job steps required to perform the work

- Determining labor required

- Determining any/all prepatory work required

- Determining all parts, materials and supplies

- Determining all equipment/tooling needs

- Determining all job permits and other pre-work authorizations, etc.

Work order scheduling Once we knew “what we needed to do” (work identification) and we knew “how to do it” (job planning) the next task was to decide “when we wanted to do the work”. Obviously, the more pre-planned work we can do, the better we can schedule that work to be done. In reality, scheduling falls in three major groupings. Those jobs that need to be done:

- Right now Emergencies, unplanned outages (i.e., systems off-line), environmental or safety hazards, etc.

- Near future Within the next few hours or days

- Distant future More than a week out

The most desirable scheduling situation for us was the distant future. Under these conditions, we could have the time to effectively plan all aspects of the job to minimize the time, materials and downtime requirements necessary to “get the right work done, the right way, for the right cost, at the right time”. Again, the more effective preventive maintenance, predictive maintenanceand other reliability centered maintenance (RCM) related tools we had in our “tool kit” the better.

Preventive/predictive optimization Although preventive and predictive maintenance activities are “the right thing to do” with the underlying focus of promoting more proactive (planned and scheduled) maintenance, too much of a good thing, we found out, isn’t effective either.

For us, these activities needed to be balanced and optimized and, therefore, provide “value” for the time and effort they required. This wasn’t an easy task, either, and required a lot of resources to accomplish since we had typically failed to perform any such “balancing and optimizing” efforts for months-on-end or even years.

Materials coordination One of the biggest cost contributors to any work we do, is the parts and materials required to do the job. What’s even more costly is maintaining these items in inventory; paying the associated storage and handling costs; carrying more than what we need; not carrying critical items; spot buying; overnight freight charges, etc. Obviously, there’s a cost for carrying “too much inventory”, as well as for downtime and, in some cases, lost revenues, for carrying “too little inventory”.

Scheduled outage/shutdown coordination In a more proactive work environment, it’s easier to predict what parts/materials we need for what work when we have extra lead-time as a result of effective planning and scheduling processes. These processes include scheduled downtime to perform needed predictive and preventive maintenance. This was clearly the most effective and efficient route for us to go.

Conclusion

A sound Asset Maintenance Management Strategy has to be viewed as belonging to, and involving, the entire organization not just the maintenance department. We at Macon Water Authority have successfully started our journey towards a sound, effective and efficient AMMS by putting in place “best business practices” with regards to our asset maintenance.

We’re now incorporating those best business practices in the configuration and set-up of our new CMMS. These documented best business practices, coupled with our new CMMS system, will allow us to reduce maintenance costs, minimize unscheduled downtime, improve service reliability and extend the lifecycle of our assets.

Authors’ Notes:

Tony Rojas is executive director of the Macon Water Authority in Macon, Georgia, USA.

Jim H. Davis is operations director of Performance Consulting Associates of Atlanta, Georgia. With over 20+ years of work experience and background in electric utilities, water and wastewater treatment plants, aviation, mining and both discreet and process manufacturing operations, he’s a Certified Maintenance & Reliability Professional (CMRP) with the Society of Maintenance & Reliability Professionals.

Contact: +1-770-717-2737, [email protected] or www.pcaconsulting.com