Day Zero moves forward as Cape Town’s water supplies run dry

CAPE TOWN, South Africa – Cape Town residents will soon be asked to survive on minimal water consumption to help desperately hold off the severe water crisis.

‘Day Zero’ – the date forecast by the local government when Cape Town runs out of water – has now been moved forward to April 12th due to a drop in the dam levels.

A dashboardon the City of Cape Town government’s website shows progress on water conservation efforts. Currently 41 percent of ‘Capetonians’ are using less than 87 litres per day but from February, residents will be asked to use 50 litres of water per person daily.

Several reasons have contributed to what is being considered the Western Cape’s worst drought in over 100 years.

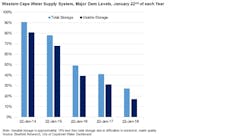

Cape Town’s population has expanded to over four million people in 2018 from 2.4 million in 1995, yet the city’s dam storage meanwhile has only increased by 15 percent.

Furthermore, water consumption has increased while the region has received below average rainfall. Simply put: water demand has outpaced water supply.

International best practise

In a statement, Ian Neilson, deputy mayor said: “It is still possible to push back Day Zero if we call stand together now and change our current path.”

Currently a ‘Critical Water Shortages Disaster Plan’ is being drafted for April. Neilson said this “draws on international best practices” and reflects “what other cities around the world have implemented when faced with extreme drought conditions”.

Meanwhile Helen Zille, premier of the Western Cape, recently outlined plans for Day Zero in a column for the Daily Maverick.

She said: “As we begin the countdown to Day-Zero, the ground has shifted. While we must still do everything possible to prevent this ghastly eventuality (and we still can if EVERYBODY abides by the new water restrictions of 50 litres per person per day), my focus has shifted to overseeing plans for the day the taps run dry – and the weeks that follow.”

Day Zero plan

If the Day Zero eventually is reached, the following would happen.

One week before the six dams providing water to the Western Cape Water Supply System drop to 13.5 percent, a date will be announced when all taps in Cape Town’s residential suburbs will be cut off.

From that point, municipal water will only be available at 200 points of distribution (PoDs) across the city.

The maximum allocation will be 25 litres per person per day, distributed on the assumption that an average family comprises four persons. For larger families, proof of additional numbers may be needed through identity documents.

Zille warned however that such plans could create a “logistical nightmare”, suggesting that if every family sends one person to fetch the water allocation, there would be 5000 people at every POD daily.

Back in November city executive mayor Patricia de Lille said these sites would be extended or include 24-hour operations to cater to such crowds.

Furthermore, people would have to carry 100 litres of their water allocation by hand – practically impossible - meaning the provision will have to be made for transport.

Political pressure

With questions being raised as to how the situation is being handled by local authorities, it’s important to note the political situation in the region.

The Western Cape is the only province in the country run by the Democratic Alliance, the official opposition party. Meanwhile, South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC) controls the rest of the country, including the National Department of Water and Sanitation (NDWS), which maintains regulatory control over agricultural water use.

Although the city of Cape Town has been under pressure to implement water restrictions, the “agricultural takings have been less controlled”, according to Will Maize, senior research analyst at Bluefield Research.

Data from the city government shows that while residential water consumption is on target with planned usage, agricultural usage is still above what has been planned.

News24 reported that in 2015, nearly 40 percent of Western Cape's water supply went to agriculture, particularly long-term crops such as fruit and wine, as well as livestock.

Although the local tiers of governance - Western Cape province and City of Cape Town - went "above and beyond" to prepare for drought, the system failed at the "level of national government", the report said.

Maize told WWi magazine: “Long-term planning processes require re-thinking amidst an increasingly volatile water cycle. Designing resilient water supply systems requires diversification of water supply sources; augmenting surface and ground water supplies with desalination, and even more-so, water reuse. It is also important that regulators – from national to municipal or city level, align policies to ensure that conservation efforts are fair, equitable, and apolitical.”

The city has made good progress with reducing water losses. In total, from 2012 pressure management and pipe replacement efforts have provided Cape Town an estimated 54,400 m3/day – a 7.1% supply boost under normal conditions.

“The city has been successful with its pressure management improvements so is understandably dismayed at being dragged through the mud in the current situation,” adds Maize.

Long-term desalination plans

Several ideas have been discussed to provide emergency water supplies during the crisis. A combination of groundwater extraction and small-scale desalination is expected to provide between 120 million to 150 million litres per day.

Zille added: “As the drought is likely to persist, we will have to go for large-scale desalination in the years ahead, and we are grateful to all those entrepreneurs and consortia who have come forward to make proposals in this regard.

A feasibility study for a $1.1 billion 450,000 m3/day desalination plant for South African utility Eskom concluded in 2016 but the plans have been postponed to after 2025.

“Cape Town was contemplating desalination for a long time but wasn’t willing to pull the trigger due to high costs,” adds Maize.

For the short term, the City of Cape Town lists seven projects to help secure alternative water sources, including four desalination projects (Cape Town harbour, Strandfontein, Monwabisi and V&A Waterfront), two groundwater projects (Cape Flats and Atlantis) and a water reuse project (Zandvliet).

However, all of the projects were listed behind schedule, apart from the V&A Waterfront desalination development.

This temporary plant is expected to provide 2,000 m3/day of water and is being constructed on land made available to the city by the V&A Waterfront at no extra cost.

Beer for water

Meanwhile, South African Breweries (SAB) has committed its Newlands brewery to fill 12 million bottles with water (instead of beer) from a spring that is usually used to brew beer.

Work is currently under way between SAB and the South African Bureau of Standards to make sure the bottled water – to be labelled “Water, Not for Sale” – meets quality standards.

The SAB network will then deliver water to retail outlets in designated areas of greatest need over several weeks.

People can then pay R1 for the bottle’s deposit and when the bottle is returned, empty, it will be replaced at no charge.

###

Read more

Turning a utility into a business: tariff transformation in eThekwini, South Africa

About the Author

Tom Freyberg

Tom Freyberg is an experienced environmental journalist, having worked across a variety of business-to-business titles. Since joining Pennwell in 2010, he has been influential in developing international partnerships for the water brand and has overseen digital developments, including 360 degree video case studies. He has interviewed high level figures, including NYSE CEO’s and Environmental Ministers. A known figure in the global water industry, Tom has chaired and spoken at conferences around the world, from Helsinki, to London and Singapore. An English graduate from Exeter University, Tom completed his PMA journalism training in London.