World of water leg three: Cross-stakeholder collaboration in the Asian water sector

My third travel leg on my global exploration of water disparities took me to a new continent, Asia, where the automatic greeting when I met someone was always, “That must’ve been a long flight!” Starting in Thailand, followed by Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore, Indonesia, South Korea and Japan, my travels exposed me to completely new cultures, traditions, and concepts within the water field. I found that across the Asian continent, diverse water realities reflect distinct histories — from government ideologies and colonial legacies to disparities in sanitation infrastructure and research investment. In conversations with water experts across various organizations, it became evident that distinct histories lend themselves to distinct solutions. However, while the hyperlocality of water issues renders an “out of the box” fix impossible, sector expert networks play a crucial role in Asia and on a global scale in facilitating co-development, particularly connecting local organizations with relevant, but previously inaccessible, technologies and expertise. Encouragingly, in my travels, I encountered a multitude of promising interventions on a household, national and even transnational scale that have the potential to improve performance and resilience of global water systems.

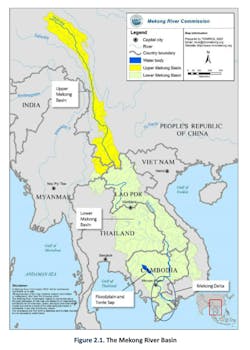

The governance of the Mekong River is one such example. As urbanization, rapid industrialization, and climate change challenge transnational waterways, creating coalitions for shared stewardship can prevent conflict. With the Mekong River stretching all the way from China through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia to the delta in Vietnam, the practices of all riparian states will influence water quality. This means that there must be cooperation of participating states in governing water uses, monitoring contamination levels, and implementing measures to protect the source. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) was founded by the governments of Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam in 1995 to do just that “for the mutual benefits of the lower Mekong countries and people’s well-being.” The commission has generally been considered a success in water diplomacy, facilitating long term basin-level planning, sharing data, and establishing water management procedures. Most recently, the MRC has been engaged in debates with non-member China regarding hydropower development upstream, with worries that the lower states will face environmental burden without economic benefits.

There are multiple organizations across Asia working to promote cross-stakeholder collaboration on scales smaller than transnational waterways. One organization pushing for engagement on a community level is Water Stewardship Indonesia (WSI), founded in 2019 in Jakarta, Indonesia. Fany Wedahuditama, Chair of the Executive Board of WSI, explained that the organization aims to develop leadership in communities to promote the knowledge and implementation of sustainable water stewardship principles. According to Wedahuditama, common methods of data collection in the water field, particularly sampling, lack the specificity of knowing who exactly has what within each community. Because of this, WSI specializes in SDG Household Data Surveys, where they work with community leaders to collect census data on metrics of drinking water and sanitation access. Ambitiously, Wedahuditama feels WSI could deliver, with government endorsement, census data to the 70,000 villages in Indonesia within a year. After the census, the data is owned by the community, with WSI offering training on how to develop data-informed proposals for grants from village funds, or even WSI and its consortium. WSI itself acts as a platform of partners that attracts donors for water and sanitation projects in Indonesia. This is a prime example of how expert networks can offer expertise to improve outcomes on a local level.

Especially in Indonesia, creating a drinking water intervention while ignoring overall sanitation realities would be a lesson in futility. This is why WSI’s work includes collaborating with key stakeholders, particularly in the private sector, on sanitation and water replenishment initiatives. One behavior that many projects aim to combat is open defecation, practiced by nearly 25 million people in Indonesia and 420 million people globally. Lack of sanitation infrastructure and wastewater treatment, along with long-established norms, lead an estimated 95% of Indonesian wastewater to leak into agricultural fields, open drains and rivers. This converts drinking water from a basic service to a threat to community health. Drinking water contaminated by raw sewage has significant health risks, including cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and polio. Diarrhea, from which a quarter of all Indonesian children under five years of age suffer, is the leading cause of child mortality in the country. The slow progress and massive scale of sanitation challenges has pushed those with the means to take matters of drinking water quality into their own hands.

Filtration start-ups have developed in this space, serving as a technological enabler for households to treat their own water. I visited with Christine Manson, the founder and CEO of Terra Water, at their headquarters on the island of Bali, where she walked me through the manufacturing of their effective, yet low resource filter. She introduced me to the simple, local materials used to craft the ceramic filter: clay, sawdust, and water. The small pore size of the ceramic material helps to trap impurities in the water, like turbidity and sediments, while a coating in colloidal silver kills bacteria, like those present in water contaminated by waste. Customers can also buy an activated bamboo charcoal filter to float in the water, adsorbing certain heavy metals and chemicals and improving aesthetic water quality. Manson explained that Terra’s filter can be customized depending on consumer preferences, including stickers with a business’ logo, high-end enamel copper coverings, and even filter stands made from recycled river plastic. Regardless of customization, the filtration technology always stays the same.

Currently, growth for Terra is limited not by demand, but by rates of production, given that finding the tedious balance of each batch of ingredients comes with a 15-25% fail rate. Manson explained that Terra currently has offerings for the extremes of the income spectrum in Bali, but that the goal would be to produce Terra filters at a price point that appeals to the middle class, estimated to be around $40 USD. TerraLite — a subsidized option for populations living in poverty — provides filters in a plastic bin, along with a public health training program. This includes information urging proper sanitation behaviors with the aim to decrease open defecation and prioritize washing hands. Manson noted that women are often the ones in an Indonesian household who have knowledge of family water habits, money expenditures, and sanitation behaviors, so Terra has adapted their educational approach to target them specifically. She explained, “The public health education program is taught for women, by women.” Overall, Terra proves that there is a space in the water sector for private businesses that enable household water needs when public supplies are inadequate.

When it comes to generating new knowledge and technologies for the public and private water sectors to leverage, it is undoubted that academia plays a role in driving forward innovation. In Seoul, South Korea, I met with Dr. Seongpil Jeong, principal researcher for the Water Cycle Research Center at the Korean Institute of Science and Technology (KIST). Dr. Jeong receives a combination of government and grant funding to pursue a wide variety of water-related research topics, focusing most recently on a treatment method with potential to more effectively remove contaminants from water resources: membrane distillation. Membrane distillation is a process whereby untreated water on one side of a hydrophobic membrane is heated to vaporization, causing the vapor to osmose through the membrane and leave non-volatile materials, like heavy metals or salt, on the other side. This is particularly relevant in Seoul, where the drinking water comes from the Han River that runs right through the city, creating concern for industrial contamination. While membranes are used widely in water treatment and desalination, Dr. Jeong’s lab has been studying how the addition of different compounds to water as a pre-treatment could improve performance and longevity of the membrane. The hope is that this academic research can promote wider scale commercialization of the technology, especially as increased global water stress increases the need for water source diversity.

Perhaps there is no better example of the application of scientific innovation in the development of a diversified national water strategy than that of Singapore. I had the chance to visit Singapore’s Sustainability Gallery, a center run by the National Water Agency, PUB, to engage with the public on water stewardship principles. Singapore’s population and economic growth, along with its lack of freshwater resources as a small island, has made it one of the most naturally water-stressed nations on the planet. Its challenges continue to worsen with climate change. To combat this, the Singaporean government developed the Four National Taps: water catchment, reclamation, desalination and imported water. By diversifying its sources of water, Singapore decreases its vulnerability to climate change and reliance on rainwater-dependent sources. Water catchment is particularly relevant in the Sustainability Gallery, as the complex sits right above the Marina Barrage, an intricate dam and gate system that maintains a freshwater reservoir right in the heart of the city. The dam not only provides an extra source of water but also helps control flooding during Singapore’s two monsoon seasons.

Despite the extreme challenges that some countries in Asia face with wastewater management, Singapore flaunts a state-of-the-art reclamation system, where wastewater is re-purified for use in industrial capacities. This NEWater diverts demand from drinking water, and can also be consumed by humans in cases of extreme drought. Along with membrane desalination, the “third tap,” these two sources make up Singapore’s rainwater independent supplies. Investing in rainwater independence will be crucial with changing climate patterns, but also to decrease current reliance on Malaysia for imported water. Under a deal signed in 1962 that expires in 2061, Singapore can draw up to 250 million gallons of raw water a day from the Johor River, and in exchange are required to provide treated water to Johor, Malaysia. Singapore buys the water for less than a cent per thousand gallons of raw water and resells it to Johor at around 11 cents per thousand gallons of treated water. This deal has been controversial due to the perceived price disadvantage of Malaysia, concerns over Johor’s water security and the limits that the deal puts on Malaysia to be able to control its own water sources. This water agreement, similar to the Mekong River Commission, is an example of how shared water resources can create a precarious balance between international cooperation and potential conflict. The complicated dynamics of water diplomacy was a strong theme across Asia.

Thus, between Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Singapore, Indonesia, South Korea and Japan, the vast differences in overall water access, quality and infrastructure make realities impossible to generalize. For a small, wealthy and tightly regulated country like Singapore, their rigorous centralized national water strategy has been highly effective in reducing their vulnerability. However, in larger countries with geographically disparate communities and with fewer funds available, other entities may be called on to implement systems, providing opportunities for companies, NGOs, and researchers to partner in facilitating local solutions. There is no-one-size-fits-all solution. What is clear, however, is that collaboration between different stakeholders in the water sector drives sustainable progress in global access, quality and conservation of water.

About the Author

Kaitlin Spiridellis

Kaitlin Spiridellis graduated summa cum laude from Vanderbilt University in May 2024, where she studied organizational studies, Spanish, and sustainability. During her time at school, she worked for three years in Vanderbilt’s Drinking Water Justice Lab, where she studied the impact of drinking water contaminants on human body organ systems within community water systems in the United States. She was awarded the Michael B. Keegan Traveling Fellowship in 2024 with a proposal to expand the efforts of the Drinking Water Justice lab globally. Currently, she is traveling across six continents conducting semi-structured conversations and site visits with researchers, NGOs, development firms and municipalities to gain a better understanding of the disparities in how people experience drinking water. She is writing about her experiences on her Substack @spiroadventures and in a column for WaterWorld.