Working Toward A More Gradual Transition From Concept to Design

By Justin Reeves

Where does most of your frustration lie when it comes to project execution? Whether you are constructing a new pipeline, rehabilitating an aging pump station, or extending a roadway, at what point in project execution does your stress level rise and doubts start to creep in?

For an owner, the dreaded change order is a likely culprit. It doesn’t matter if it is an addendum to the design consultant contract changing the schedule or increasing the scope, or if it is a change order identified by the contractor with a subsequent request for more money; the feeling is often the same and the owner is left thinking, “What happened?”

For the design engineer, the pinch point is often scope and fee negotiation. Before work even commences, the engineer sees challenges, unknowns, and risks that need to be addressed, warranting an additional fee. But the contract is written, and the work begins, with all hoping for the best.

The owner’s frustration and the engineer’s angst are often symptoms of the same disease. Not every plan is inadequate and not every process is broken, but the common approach to planning capital improvements can sometimes leave both the owner and the project team with regrets. However, if we’re willing to think just a little bit differently, this can be avoided.

The Standard Approach

Every owner develops and maintains a capital improvements plan (CIP). The popular motivational speaker Zig Ziglar once said, “If you aim for nothing, you’ll hit it every time.” Owners develop a CIP to ensure they are aiming for something. At its core, the CIP is their roadmap.

A CIP includes a prioritized or ranked list of projects, and for each project, a budget and schedule are established. Projects are developed based on the results of condition assessments, studies, and growth projections, and the plan is often devised with the help of a consultant. Typically, a CIP represents a five- to 10-year planning period.

Planning over such a long period and looking at improvements and goals for an agency or municipality requires a high-level analysis. During this process, the owner (or supporting consultant) uses generalized budget and schedule metrics from similar projects in similar geographies. But, in reality, no two projects are alike because no two geographies are identical. Thus, the high-level analysis often yields poor scope definition that rarely considers potential conflicts, risks, and unique challenges.

Yet, the CIP is developed and adopted, and the challenges begin. When a design consultant is selected for a project, he is given a budget and desired schedule from which to develop a scope and fee. The schedule is considered non-negotiable most of the time; the plan adopted by the municipality’s governing body says the project needs to be completed by a certain timeline or the level of service will suffer. Additionally, the overall budget is considered non-negotiable; funds are limited, and a cost overrun for one project means that the budget for others in the plan will suffer. So, what does the design consultant do when he sees challenges and risks for the budget and/or timeline?

Often, consultants clearly identify these challenges and present both cause and effect (scope, fee, and schedule implications). But they show the effect (higher fee) without the clear justification, unnecessarily resulting in tense negotiations. Even when consultants present clear cause and effect, the result may not be different. The budget is fixed, so the scope is reduced to align the two with all parties hoping the risks are never realized. Often, unfortunately, once the project commences, risks are realized in design or construction, resulting in extended schedules, increased costs, and frustration all around.

A Different Approach

In fairness, the CIP process described above is not the broken part. Owners and their consultants do a good job of understanding a community’s needs, developing projects to address those needs, and determining a rough order of magnitude when it comes to project cost and schedule. The design and construction phases are not broken either. The real culprit is the transition between the two.

Every owner wants a realistic budget and schedule from its consultant in the same way that every consultant wants a fair fee and reasonable schedule. But these cannot be achieved without a clear scope of work. The CIP process was never meant to deliver a well-defined scope, even though that is exactly how it is often used in going from concept to design, with design consultant engagement. A better practice is to work toward a more gradual transition from CIP concept to design.

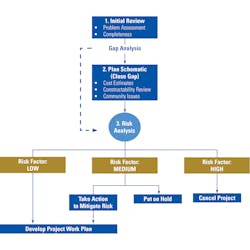

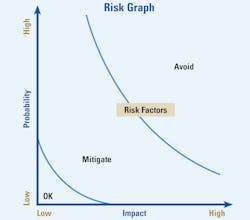

In recent years, clients have started to adopt a project development approach that has reduced project setbacks and minimized surprises. The process requires advance planning to maintain schedules and a small investment to evaluate project concepts and ideas to understand and quantify risk before engaging a design consultant. As an analogy, consider a soft opening for a new restaurant, where the doors are opened and walk ups are served. The opening is not publicized because the owner knows that kinks still need to be worked out. An investment is required; the owner knows that the immediate return on that investment is minimal but realizes that without it, frustration will ensue long-term. We can apply a similar approach with infrastructure projects as well.

Best Practices

The following summarizes some considerations in this process and best practices that have proven successful.

• Standardize: To effectively approach project development, almost every potential project needs to be put through the same analysis. This is an opportunity to develop and utilize a project development checklist to understand, for example, if consideration has been given to property needs, if record drawings have been reviewed, or if other projects in the area could be affected.

• Customize: Checklists are great and a standard review is necessary; however, every project has unique challenges, which is where the scope, cost, and schedule are taken captive. As such, reviewing geographic history, maintenance records, and local stakeholders for each potential assignment is critical.

• Use the parking lot: One of our biggest mistakes is taking the CIP and forcing ourselves to move forward even when warnings clearly pop up along the way. In this new approach to project development, you need to be willing to look at a project, see the risks or unknowns, and then press pause. By putting a project in the parking lot, you acknowledge that you aren’t ready to move it forward. It doesn’t mean admitting defeat and canceling the project; rather, it is simply saying that before we can move forward with confidence, we need more information. This practice alone can make life significantly easier as it can free up time and funds to pursue projects where you have a greater confidence in success.

• Give up sacred cows: Related to the parking lot idea is the notion that no project is sacred or untouchable. This process demands objectivity and an understanding from all parties that the CIP is a guide and not a recipe that must be followed precisely. All CIPs have priority projects, but the project development effort will never be successful if any one project is put on the untouchable pedestal.

Overall, the project development process involves looking at a series or group of planned projects through a tighter lens than the CIP effort is intended to address. It is simply not well suited to progress directly into the design phase, particularly as our infrastructure needs and challenges have grown more complex. The project development process helps bridge the gap.

Conclusion

The project development process is about overlapping planning and execution, building on an adopted CIP, and starting design with clear expectations, a well-defined scope, and a mutual understanding of project risk. The result is development and initiation of projects with realistic scopes, budgets, and schedules — meaning fewer project stops, restarts, scope changes, design amendments, and change orders.

The process is not perfect, as no process is, and it requires a different train of thought, a higher level of planning, and an earlier start to identify risks that may extend schedules or increase budgets. It requires a worthy investment outside of and before design commences that will help reduce unnecessary design amendments and change orders, ultimately improving the implementation of a CIP and gaining the trust and confidence of the community. WW

About the Author: Justin Reeves, P.E., is a senior associate at Lockwood, Andrews & Newnam Inc. (LAN), a national planning, engineering and program management firm. He has more than 15 years of experience designing water and wastewater pipelines. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Justin Reeves

Justin Reeves, P.E., is a senior associate at Lockwood, Andrews & Newnam Inc. (LAN), a national planning, engineering and program management firm. He has more than 15 years of experience designing water and wastewater pipelines. He can be reached at [email protected].