World of water leg four: No option is off the table in Australia

Key Highlights

- First Nations communities in Australia face significant disparities in water access and quality, often linked to historical and environmental racism.

- Climate change introduces non-stationarity, complicating water resource management and requiring improved models like CMIP to predict future variability.

- Australian utilities are investing in rainfall-independent sources such as desalination and water reuse to mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events.

- Decentralized governance across states and territories results in diverse priorities and technological approaches to water management.

- Public engagement and education are crucial for acceptance of recycled water projects, with tools like Sydney’s demonstration plants fostering trust and transparency.

Across Latin America, Europe and Asia, most of my research has focused on the disparities of access to and quality of drinking water that exist between nations. However, my visit to Australia demonstrated that decentralization of governance and regulation within a nation can also create vastly different internal realities.

In visiting Sydney and Melbourne, notably only two major cities in an incredibly complex geography and only one part of the vast Oceania region, three key themes emerged. One: the nation's most isolated and rural communities, particularly First Nations groups, are struggling with a gap in utilities meeting their most basic needs. Two: current global climate models are not well-adapted to the non-stationarity posed by climate change, struggling in their role of accurately identifying and forecasting weather events and trends. Three: many Australian municipalities are investing heavily in rainfall-independent sources, such as desalination and water reuse, as precipitation becomes more extreme and less predictable.

Australia’s six states and two territories make it the sixth largest country in the world, and in speaking with experts across the country from utilities, industry boards, research centers and universities, the diversity and vastness of the landscape intensely complicate how drinking water is sourced, governed and experienced across the country. While some utilities, like Sydney Water, service millions of households with extensive resources and expertise, other utilities for much smaller communities are run by only a handful of employees.

One organization working to bring together otherwise disparate utilities across Australia and New Zealand is the Water Services Association of Australia (WSAA). The WSAA creates opportunities for information sharing, collaborative forums, and collective catchment management, while also advocating on behalf of the utilities to the media and government. With unbridled visibility across the value chain of water in Australia, the WSAA is also well positioned to highlight key trends and strategic initiatives across the national water sector, as it did with Strategy 2030.

One of five strategic priorities in the WSAA’s Strategy 2030 is a focus on reducing disparities in services for First Nations groups. First Nations groups are the communities indigenous to the country and are vast in number and diversity. Many faced a level of brutality and subjugation at the hands of colonial settlers that the country is still coming to terms with today.

When I spoke with Taylor Hayward, the First Nations Lead at WSAA, he explained that current disparities that First Nations groups experience today with their drinking water, whether a lack of access or unacceptable levels of microbial or chemical pollution, is a modern-day manifestation of historical racism. One could draw parallels between the Australian context and the impacts of environmental racism felt in the United States today by many of our most vulnerable communities, as highlighted by respected environmental sociologist Dr. Dorceta Taylor in Toxic Communities.

While WSAA’s Strategy 2030 was an important step in acknowledging the disparity that First Nations groups can experience, Hayward explained that a lack of data and engagement with these communities makes progress fragmented and slow. An article published in 2022 by the University of Queensland School of Public Health explained that more than 500 remote Indigenous communities do not have their tap water regularly tested. Of 84 remote Aboriginal systems in Western Australia that were found to have shortcomings in a 2015 audit, the Auditor General reported that 37 of them still remained at risk of unsafe water by 2019-2020.

Community water systems tested positive for contaminants like E.coli, nitrates and uranium. In Western Australia, where Hayward lives, he explained that the state has mechanisms to provide these First Nations groups with services but often uses the excuse of it being too expensive or remote. Hayward noted however that many remote, small communities that were historically European or agricultural settlements rather than First Nations groups have been serviced adequately since their formation.

Therefore, Hayward advocates for adhering to the same principles of service for each community regardless of historic identities, while backing it up with increased federal funding to subsidize utilities in their efforts. Importantly, due to the vast diversity within and between First Nations groups, localized co-development of water interventions is crucial to ensure that approaches are feasible and acceptable within cultural practices and values. What is needed, ultimately, as the University of Queensland article puts it, is “a system that is fit for purpose, place and people.”

Water systems in Australia will have stressors exacerbated by climate change, which is redefining what is considered normal in the water field. Non-stationarity was mentioned quite a bit in my meetings, defined as changing relationships in direction or magnitude between variables over time. In Australia, for instance, it will be crucial to understand how climatic warming will impact extreme rainfall events, both for reservoir management and for flood prevention measures.

Non-stationarity presents a significant challenge for climate statisticians who struggle to adapt their models to incorporate changing relationships between variables. Dr. Keirnan Fowler, a senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne within their Environmental Hydrology and Water Resources Group researches climate change risk estimation to help water industry partners better predict the challenges they will face in the future.

Dr. Fowler introduced me to the concept of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP), which is a data infrastructure run by the World Climate Research Program to provide projections for past, present and future climate scenarios. Progressive CMIP generations help to improve global climate models, although Dr. Fowler highlighted two necessary areas for CMIP improvement: variability and rainfall.

He explained that Australia has a highly variable environment, with multi-year dry or wet spells that are important to factor into models for reservoir levels. As current climate models struggle with multi-year variability and non-stationarity, they can create a biased view of future quantities of available water. Dr. Fowler was ultimately confident that CMIP was headed in the right direction to addressing such limitations.

Increased variability and unpredictability of weather patterns are pushing Australian water organizations to be increasingly innovative in their technological solutions, with a focus on rainfall independent water supplies. I spoke with Jacqui Levy, Water and Public Health Senior Advisor at Sydney Water, the city’s main utility.

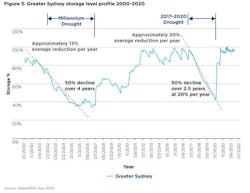

Since Greater Sydney relies on rainfall for 85% of its total supply, the city is vulnerable to climate shifts and droughts. She explained that the Millenium Drought, one of the most intense droughts in Australian history between late 1997 and 2009, led to a drive for more recycled water for non-potable uses, such as watering lawns, golf courses and sporting fields, to decrease demands on drinking water. However, from a cost perspective, the real benefits come from the economies of scale that community drinking water systems offer.

Levy explained that Sydney Water, WaterNSW (who owns the water at the source), and the New South Wales Government have made it clear that there is “no option off the table” when it comes to future-proofing their water supply, including water recycling and desalination. This is highlighted in the Greater Sydney Water Strategy, which even discusses the capture and reuse of stormwater as a priority. This, while less intensely implemented, aligns with Singapore’s strategy of utilizing every drop of water, no matter if it comes from wastewater, stormwater or the ocean.

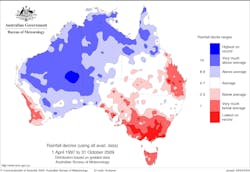

Interestingly, as seen in the Bureau of Meteorology map below, Australia contains such diverse landscapes that intense drought conditions in Sydney were paralleled with relatively high rainfall levels in other areas of the country. This climate diversity contributes to differing levels of commitment and prioritization of rainfall independence schemes, which is exacerbated by the decentralization of governance between the states and territories.

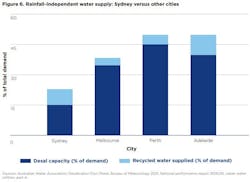

Luckily when it comes to recycling water, Sydney has many examples domestically and internationally to follow, from Perth, Australia to Singapore and Orange County, California. In Perth, for instance, the Beenyup Advanced Water Recycling Plant has been treating wastewater to a potable standard; and then injecting it into the Yarragadee aquifer.

When the utility pulls from this aquifer, Perth is indirectly reusing treated wastewater for drinking water. The groundwater replenishment scheme in Perth has been greatly successful, providing enough water for 100,000 households, but also pioneering Australian water reuse and serving to form its governing guidelines.

The Perth Integration Water Supply Scheme helps to protect aquifer health, but the indirect nature of the reuse also aids public perception by allowing the city to distance itself from the “toilet to tap” narrative that makes the public cautious of drinking recycled water. In fact, the water at the Beenyup Wastewater Treatment Plant goes through rigorous testing throughout the entire treatment process, including ultrafiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet disinfection.

When water is later pulled from the aquifer, it also goes through the traditional treatment that normal groundwater would go through. Public opposition comes, occasionally, from a lack of public engagement and education on the topic by the utilities.

The WSAA has created a toolkit for utilities implementing new recycled water plants, called “Lessons on the Journeys of Others,” highlighting strategies that prioritize time, trust and transparency when trying to gain public support. In Sydney, this is reflected in the Quakers Hill Water Resource Recovery Plant, a demonstration site to educate the public, particularly youth, and train new people on water reuse technology.

While wastewater can be an input for recycled water, it is also a tool for resource recovery, a central priority in Australia currently. Dr. John Radcliffe, honorary fellow at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization and former Chair of the Research Committee of the Australian Water Recycling Center of Excellence, explained how the water-energy nexus contextualizes the various applications for recycled water along all steps of treatment, whether the wastewater will be dumped far out into the ocean or ultimately repurified for direct or indirect potable reuse.

He mentioned a $1.7m pilot project at Yarra Valley Water to confirm technology that uses recycled water to generate green hydrogen. Green hydrogen can be produced through electrolysis, using electricity to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen gas can then be stored for use in fuel cells for a clean energy resource.

The Australian government has introduced a temporary measure, called the Hydrogen Production Tax Incentive, that could potentially offset initial investments in resource recovery by utilities. Dr. Radcliffe even mentioned deepwater ocean outfalls, like the ones that Sydney Water uses to dump its treated wastewater, as a tool for generating electricity from hydropower. From nutrient and biosolid recovery to reduced emissions, a focus on resource recovery is another reason why wastewater has turned from a liability to an opportunity in the increasingly circular Australian water sector.

The vast diversity of Australian communities, both culturally and geographically, makes it impossible to generalize overall priorities and strategies, but key themes, such as First Nations’ disparities, the issues with non-stationarity in climate modeling, water recycling and resource recovery did emerge numerous times in meetings with water experts. Decentralization of water governance between states and territories also means that different Australian regions have diverse investment priorities and technological focuses.

Given significant climatic challenges that are being faced and will continue to emerge in Australia and across other nations on Oceania, the rallying cry “No option off the table” in the Greater Sydney Water Strategy is by no means dramatic. But rather, it accurately reflects the necessity of innovative development and investment in the water sector to protect and find new sources of drinking water in a very uncertain future.

About the Author

Kaitlin Spiridellis

Kaitlin Spiridellis graduated summa cum laude from Vanderbilt University in May 2024, where she studied organizational studies, Spanish, and sustainability. During her time at school, she worked for three years in Vanderbilt’s Drinking Water Justice Lab, where she studied the impact of drinking water contaminants on human body organ systems within community water systems in the United States. She was awarded the Michael B. Keegan Traveling Fellowship in 2024 with a proposal to expand the efforts of the Drinking Water Justice lab globally. Currently, she is traveling across six continents conducting semi-structured conversations and site visits with researchers, NGOs, development firms and municipalities to gain a better understanding of the disparities in how people experience drinking water. She is writing about her experiences on her Substack @spiroadventures and in a column for WaterWorld.