Transforming potable water supply: VVater’s approach to industrial and municipal reuse

A Fortune 50 food and beverage facility announced it is converting 40,000 gpd of impaired water into potable supply, signaling what could be a turning point for utilities, reuse, and decentralized drinking water infrastructure. Read the press release.

As climate variability, drought, and regulatory pressure strain traditional drinking water systems, utilities are being forced to rethink where potable water comes from — and how resilient that supply truly is. Increasingly, the future of drinking water is not only about treatment at centralized plants, but about advanced purification at the point of use.

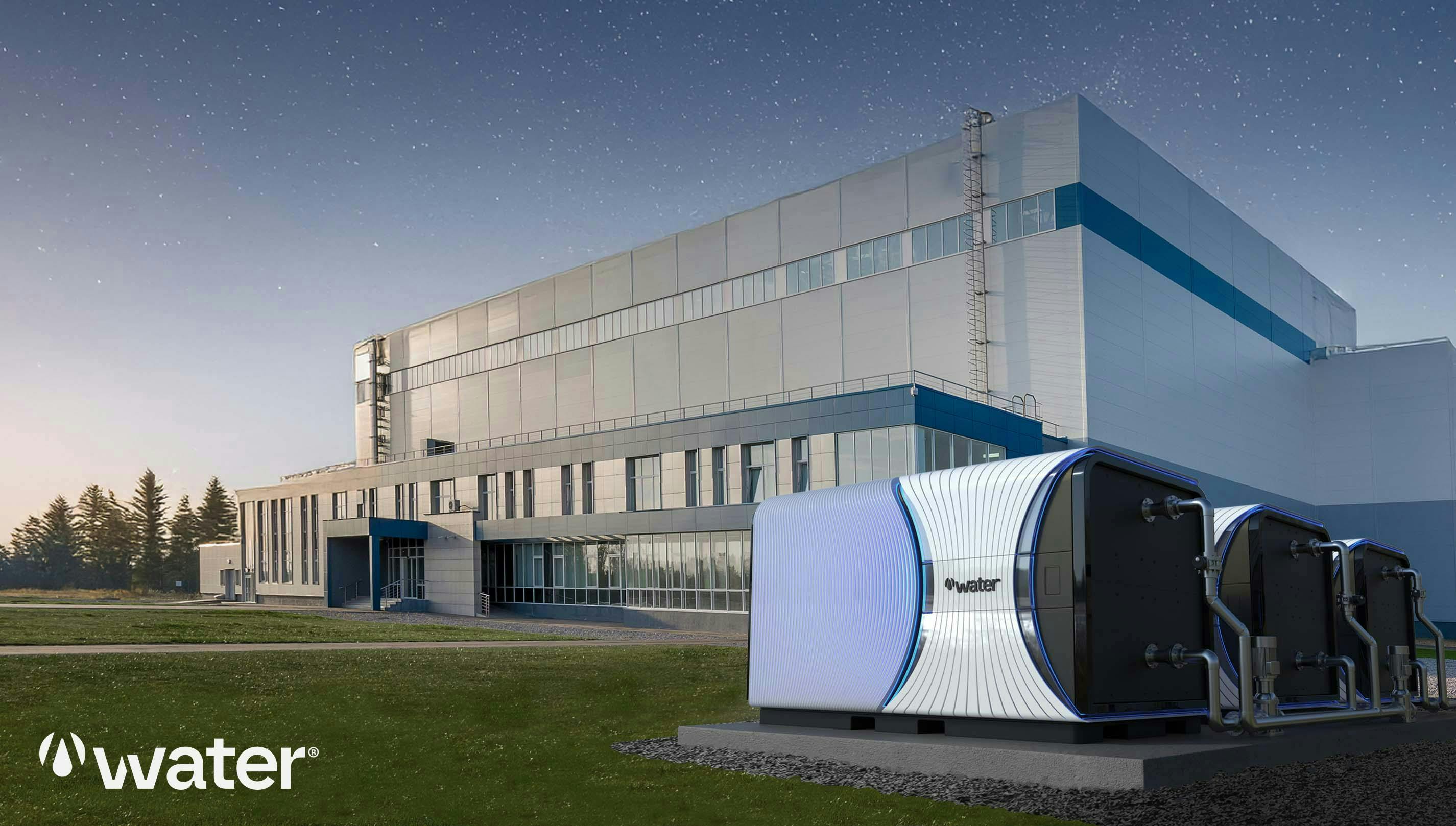

A new project led by VVater illustrates how industrial reuse technologies are beginning to blur the line between “industrial wastewater” and “drinking water supply.” In January 2026, VVater announced a 10-year, multimillion-dollar contract with a Fortune 50 food and beverage manufacturer in Texas to convert 40,000 gallons per day of previously contaminated industrial water into potable-quality water using its Farady Reactor technology.

While the project is located at an industrial facility, its implications are highly relevant for drinking water professionals: it demonstrates how modular, decentralized purification systems can reliably produce potable-grade water from impaired sources — at scale, on compressed timelines, and with a smaller footprint than conventional treatment trains.

For utilities exploring direct potable reuse (DPR), indirect potable reuse (IPR), and distributed treatment, this project provides a real-world example of how advanced electrochemical and physical treatment can complement or even supplement traditional centralized infrastructure. It also highlights how private-sector innovation may increasingly intersect with public drinking water systems as communities seek resilient, locally controlled supplies.

This project also reflects a broader shift in how potable water is being conceptualized: less as a one-way product delivered from distant reservoirs, and more as a circular, locally managed resource that can be continuously purified, reused, and safeguarded.

WaterWorld (WW) partnered with our friends at Water Technology to cover the industrial side of this project in depth. Read the industry-focused Q&A: Decentralized treatment technology transforms Fortune 50 F&B company's water management.

Below, read the Q&A with VVater Chairman and CEO Kevin Gast, with a focus on what it means for drinking water, reuse, and public-sector systems.

WW: From a treatment and operations standpoint, what were the biggest water quality and regulatory challenges at this facility, and how did VVater’s system address them compared to more conventional industrial treatment approaches?

Gast: At this facility, the primary challenges were rising discharge costs, tightening regulatory limits, and the long-term sustainability of land application as a wastewater management strategy. These challenges reflect broader trends across the industrial sector, where manufacturers are facing increasing regulatory scrutiny, higher disposal costs, and growing pressure to reduce freshwater consumption while maintaining operational reliability.

VVater’s system addressed these challenges by enabling on-site conversion of used industrial water into potable-quality water suitable for internal reuse, shifting the focus from disposal to recovery. Compared to conventional industrial treatment approaches that rely heavily on chemical dosing, large footprints, and multi-stage separation processes, VVater’s approach emphasizes advanced treatment, compact system design, and reduced operational complexity, allowing facilities to minimize discharge exposure, improve regulatory flexibility, and significantly reduce reliance on external water supplies.

WW: This project converts 40,000 gallons per day of used industrial water into potable-quality water. What does that process look like in practice, and what should water professionals understand about operating and maintaining a closed-loop system at this scale?

Gast: In practice, the system operates as a continuous-flow, closed-loop treatment process that upgrades used industrial water to potable-quality standards suitable for internal reuse. The treatment approach emphasizes advanced contaminant destruction, microbial control, and system stability, allowing the facility to recover water that would otherwise require discharge.

For water professionals, the key consideration at this scale is operational predictability. Closed-loop reuse systems must be designed to handle variable influent quality while maintaining consistent output. This requires robust automation, real-time monitoring, and reduced reliance on consumables such as chemicals and disposable filtration media, which can introduce operational risk and maintenance burden.

WW: You’ve emphasized rapid deployment by designing, building, and commissioning systems in weeks rather than years. What elements of VVater’s modular and vertically integrated model make that possible, and where do you see traditional infrastructure projects losing the most time?

Gast: Rapid deployment is enabled by VVater’s modular system architecture and vertically integrated delivery model, which allow engineering, fabrication, controls integration, and testing to occur in parallel rather than sequentially. Core system components are pre-engineered and assembled off-site at VVater’s facilities in Austin, Texas, significantly reducing the need for extensive civil work, long construction schedules, and complex field integration.

This approach is supported by highly experienced engineering and operations teams with backgrounds across industrial water, process engineering, and advanced treatment systems. Because design, manufacturing, and commissioning are tightly integrated, systems can be modified and tuned as needed for specific water quality conditions or operational requirements without restarting lengthy design or procurement cycles. Our Farady Reactors, especially our latest Gen 3 units, can be manufactured in record time due to their simplicity. Our objective is to take exceptional complex systems and simplify them to singular components.

By contrast, traditional infrastructure projects often lose time in custom design iterations, chemical system engineering, multi-vendor coordination, permitting dependencies, and extended on-site construction. A modular, vertically integrated approach compresses these timelines and allows capacity to be deployed quickly, validated rapidly, and expanded incrementally as operational needs evolve.

WW: Many industrial operators are facing rising discharge costs, stricter regulations, and water scarcity at the same time. How do you see on-site reuse and decentralized treatment reshaping water management strategies for large manufacturers over the next decade?

Gast: On-site reuse and decentralized treatment are becoming strategic infrastructure decisions rather than optional sustainability initiatives. For large manufacturers, the ability to recover and reuse water internally reduces exposure to rising water costs, discharge constraints, regulatory uncertainty, and dependence on external water supplies.

What was once framed as a long-term sustainability goal is now an operational reality. While much of the industry conversation continues to focus on maintaining aging centralized water systems and reducing distribution losses, industrial reuse is increasingly recognized as a practical strategy for improving water efficiency and supply resilience.

Over the next decade, this shift is expected to accelerate as water scarcity, permitting limitations, and public scrutiny intensify. Industrial water reuse benefits not only operators through lower long-term costs and improved reliability but also surrounding communities. In many regions, industrial development is increasingly met with public opposition driven by concerns over depletion of local water sources. By minimizing net water withdrawals through reuse, manufacturers can reduce pressure on shared resources, helping preserve water availability for municipal and agricultural users, and supporting long-term regional water stability. In this way, VVater’s decentralized treatment systems contribute to a practical circular water economy that aligns industrial growth with community resilience.

WW: VVater is expanding from industrial applications into municipal drinking water, DPR/IPR, and other sectors. What lessons from this Fortune 50 food and beverage project are most transferable to utilities and water professionals working in public-sector systems?

Gast: Several lessons from this large food and beverage deployment are directly transferable to public-sector applications. First is the value of modular system design, which allows advanced treatment to be implemented within constrained sites where physical space is limited. Second is the importance of reducing operational complexity, particularly as utilities contend with workforce limitations and aging assets.

Finally, the project demonstrates how advanced treatment and reuse can be implemented within existing facilities without extensive footprint requirements. VVater brings direct experience working within regulated environments and designing systems to meet stringent drinking water and reuse standards, which is critical for public-sector implementation. VVater’s systems are designed to integrate with existing infrastructure, providing added redundancy and operational flexibility without disrupting current treatment processes. This approach minimizes downtime, which is essential in public-sector environments where service interruptions directly impact customers. While public-sector systems operate under different regulatory frameworks, the underlying challenges of water scarcity, regulatory compliance, and operational reliability are shared across sectors, making these lessons broadly applicable.

Listen to the Talking Under Water podcast episode with Gast

TUW co-host, WaterWorld editor-in-chief talks with Kevin Gast, co-founder, CEO, & chairman of VVater, about electricity-based technology that purifies water without chemicals, filters, or membranes, offering a sustainable and resilient alternative to traditional methods may be the future.

Learn with me: related regulations explained by Carollo Engineers

In this interview, John Rehring, Vice President and Senior Project Manager at Carollo Engineers, discusses how discharge avoidance is shaping potable reuse projects in the western U.S. Rehring explains that increasingly stringent wastewater discharge permits — covering temperature, salinity, and nutrients — are pushing utilities toward alternatives that reduce or eliminate discharges.

About Kevin Gast

Kevin Gast

Co-Founder, CEO, & Chairman of VVater

The editor recieved assistance with the summary portion of this article from generative AI.

About the Author

Mandy Crispin

Mandy Crispin is the editor-in-chief of WaterWorld magazine and co-host of water industry podcast Talking Under Water. She can be reached at [email protected].