EPA Proposes First National Drinking Water Standard for Perchlorate: What Utilities Need to Know

EPA is accepting public comments on the proposed rule through March 9, 2026, and will host a virtual public hearing on Feb. 19, 2026.

Full details below.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has proposed a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for perchlorate, a move that could introduce new monitoring and compliance requirements for public water systems nationwide.

The proposal comes in response to a D.C. Circuit Court decision directing EPA to regulate perchlorate under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Under a consent decree, the agency must sign a final rule by May 21, 2027.

While EPA previously determined in 2020 that federal regulation of perchlorate was not warranted — citing low occurrence and high compliance costs — the court ruling requires the agency to revisit that position through formal rulemaking.

What is perchlorate and why does it matter?

Perchlorate is both a naturally occurring and manufactured chemical used in rocket fuel, fireworks, and explosives. It can interfere with iodine uptake in the thyroid, raising particular concerns for infants, pregnant women, and people with thyroid conditions.

In its proposal, EPA establishes a health-based maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) of 0.02 mg/L (20 parts per billion, or 20,000 parts per trillion). The agency is seeking public comment on three possible enforceable MCLs:

- 0.02 mg/L (20,000 ppt)

- 0.04 mg/L (40,000 ppt)

- 0.08 mg/L (80,000 ppt)

For context, the 2024 federal PFAS MCLs range from 4 to 10 parts per trillion — orders of magnitude lower than the perchlorate levels under consideration.

EPA’s own analysis indicates perchlorate generally does not occur in most public water systems at levels posing widespread public health concern. The agency also notes that the quantified benefits of regulation may not outweigh the costs. Nevertheless, EPA is proceeding to fulfill its legal obligation and gather updated input from states, utilities, and other stakeholders.

Share your utility's Perchlorate situation in this two question, anonymous poll

Proposed “Binning” Approach: How Monitoring Would Work

One of the most utility-relevant elements of the proposal is a new binning system designed to reduce long-term monitoring burdens based on initial sample results.

EPA would sort systems into three bins using samples collected before the rule’s compliance date (generally three years after the final rule is issued):

Bin 1 — Lowest detections (≤ 4,000 ppt)

If all initial samples at an entry point are at or below 4,000 ppt, the system would automatically qualify for reduced monitoring of once every nine years after the compliance date.

EPA selected this threshold because it is far below even the lowest proposed MCL (20,000 ppt). However, states could still require more frequent sampling if warranted—for example, if there are known local sources of perchlorate or high variability in results.

Bin 2 — Detects above 4,000 ppt but below the MCL

Systems with any sample above 4,000 ppt but at or below the MCL would move to routine monitoring:

- Surface water systems: annual sampling

- Groundwater systems: sampling every three years

Bin 3 — Any sample above the MCL

If any sample exceeds the MCL, the system would be placed on quarterly monitoring starting at the compliance date.

How systems can move to reduced monitoring

Utilities placed in Bin 2 or 3 could eventually qualify for reduced monitoring, but only through a formal state waiver process.

At minimum, systems must first complete:

- Groundwater systems: at least two quarterly samples

- Surface water systems: at least four quarterly samples

If results show the system is “reliably and consistently” below the MCL, utilities must then complete three additional rounds of annual (surface water) or triennial (groundwater) monitoring before applying for a waiver.

Only after that sequence could a system shift to the nine-year reduced monitoring schedule.

Listen to the article

What counts as “initial monitoring”?

A critical detail for utilities is that EPA would allow use of historical data collected after January 1, 2021, as long as samples were taken before the rule’s compliance date.

To qualify for Bin 1 from day one, systems must have already collected:

- Groundwater systems serving > 10,000 people and all surface water systems:

- Four quarterly samples at each entry point to the distribution system

- Groundwater systems serving ≤ 10,000 people:

- Two samples within a 12-month period, taken 5–7 months apart

If those records exist and meet quality requirements, systems could enter the reduced monitoring tier immediately.

EPA estimated in 2020 that perchlorate laboratory testing costs range from $55 to $175 per sample, depending on the method and laboratory used.

Bin 1 Automatic Reduced Monitoring: By the compliance date for groundwater systems serving > 10,000 people and all surface water systems

Bin 1 Automatic Reduced Monitoring: By the compliance date for groundwater systems serving ≤ 10,000 people

Public comment and next steps

EPA is accepting public comments on the proposed rule through March 9, 2026, and will host a virtual public hearing on Feb. 19, 2026.

Utilities, state regulators, consultants, and laboratory professionals are encouraged to review the proposal and submit feedback — particularly on:

- The three potential MCL options

- The 4,000 ppt binning threshold

- Monitoring frequencies

- Use of historical data

- Laboratory costs and capacity

The full proposal, background materials, and comment instructions are available in the Federal Register.

Learn with Me

Rulemaking Context: The Executive Orders and Statutes Shaping EPA’s Proposal

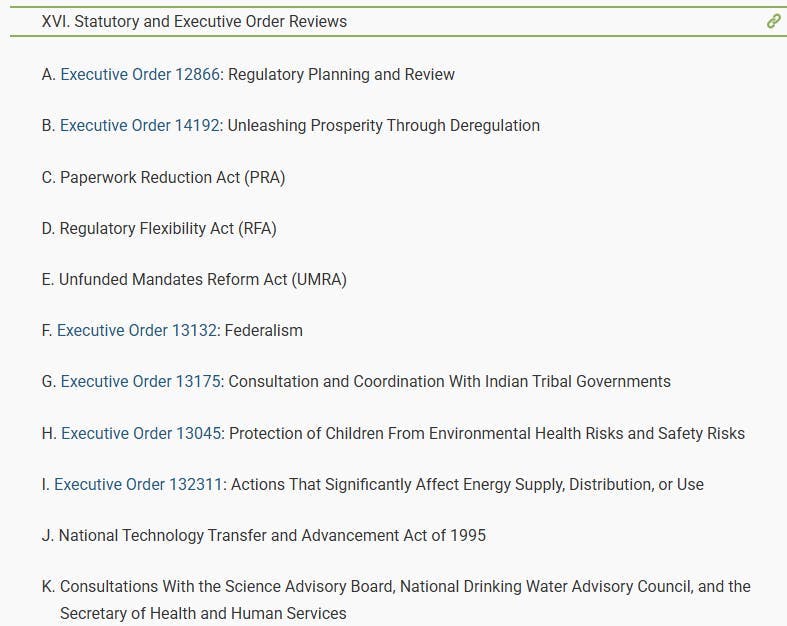

Beyond the technical details of monitoring and compliance, EPA’s perchlorate proposal also reflects a broader regulatory landscape shaped by a series of executive orders and federal statutes spanning more than four decades — and multiple presidential administrations.

These directives do not set the perchlorate standard itself, but they frame how EPA must analyze costs, consult stakeholders, consider state authority, and weigh economic and administrative burdens while developing the rule.

Taken together, they illustrate the political and policy “zeitgeist” in which this proposal is being crafted.

A cross-administration regulatory framework

The executive orders and statutes cited in the proposal stretch from the Carter administration through President Trump’s second term, encompassing both Democratic and Republican priorities.

A. Sep 30, 1993 William J. Clinton Executive Order 12866 Regulatory Planning and Review

B. Jan 31, 2025 Donald J. Trump (2nd Term) Executive Order 14192 Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation

C. May 22, 1995 Enacted by Congress during the William J. Clinton Administration Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA)

D. Sept 19, 1980 Enacted by Congress during the Jimmy Carter Administration Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA)

E. Mar 22, 1995 Enacted by Congress during the William J. Clinton Administration Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA)

F. Aug 4, 1999 William J. Clinton Executive Order 13132 Federalism

G. Nov 6, 2000 William J. Clinton Executive Order 13175 Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments

H. Apr 18, 1997 William J. Clinton Executive Order 13045 Protection of Children From Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks

I. May 18, 2001 George W. Bush Executive Order 13211 Actions Concerning Regulations That Significantly Affect Energy Supply, Distribution, or Use

J. Mar 7, 1996 Enacted by Congress during the William J. Clinton Administration National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act of 1995

K. Consultations With the Science Advisory Board, National Drinking Water Advisory Council, and the Secretary of Health and Human Services

For a list of all Executive Orders by Presidential administration, go to Universtiy of California at Santa Barbara's The American Presidency Project.

Key influences include:

Clinton-era regulatory guardrails (1993–2000)

Several foundational principles guiding modern rulemaking stem from President Bill Clinton’s administration:

- Executive Order 12866 (1993) established the core cost–benefit framework for federal regulations. It requires EPA to clearly define problems, assess alternatives (including non-regulation), rely on the best available science, and minimize unnecessary compliance burdens while still protecting public health.

- Paperwork Reduction Act amendments (1995) reinforced the need to limit unnecessary reporting and administrative burdens on utilities and states.

- Regulatory Flexibility Act (1980, strengthened in 1996) requires EPA to evaluate impacts on small systems and consider less burdensome alternatives where possible.

- Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (1995) calls for transparency around costs imposed on state and local governments.

- Executive Order 13132 (1999) emphasizes respect for state authority in environmental regulation and requires consultation when federal rules significantly affect state programs.

- Executive Order 13175 (2000) requires meaningful consultation with Tribal governments on rules that affect Tribal communities.

Bush-era energy considerations (2001)

- Executive Order 13211 requires EPA to assess potential impacts of major rules on energy supply, distribution, and costs — an important consideration for treatment technologies that may increase power demand.

Child health focus (Clinton, 1997)

- Executive Order 13045 directs agencies to pay special attention to environmental risks affecting children—relevant here because perchlorate is particularly concerning for infants and pregnant women.

Technology and standards alignment (1995)

- The National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act encourages federal agencies to work with industry standards bodies and facilitate technology transfer from federal laboratories — relevant as utilities consider analytical methods and treatment options.

Trump-era deregulatory lens (2025)

- Executive Order 14192 (2025) introduces a “regulatory budget,” requiring agencies to offset new regulations by eliminating existing ones and keeping net regulatory costs below zero where legally permissible. EPA must navigate this requirement while still complying with the court mandate to regulate perchlorate.

What this means for water systems

For drinking water professionals, these layered requirements help explain why the perchlorate proposal includes features like:

- A binning approach to reduce monitoring burdens,

- Use of historical data to avoid unnecessary resampling,

- Flexibility for states to adjust monitoring where warranted, and

- Multiple MCL options rather than a single number.

In short, the rule reflects not only public health science, but also a balancing act among legal obligations, federal–state relationships, economic impacts, and evolving presidential priorities.

EPA’s consultation with the Science Advisory Board (SAB), the National Drinking Water Advisory Council (NDWAC), and the Secretary of Health and Human Services—as required under the Safe Drinking Water Act—further underscores that this proposal has been shaped through formal scientific and stakeholder review before moving toward a final rule.

This Learn with Me summary was created with the help of generative AI.

About the Author

Mandy Crispin

Mandy Crispin is the editor-in-chief of WaterWorld magazine and co-host of water industry podcast Talking Under Water. She can be reached at [email protected].